![str1]()

![str1]()

![Lanabecestat.svg]()

![str1]()

![str1]()

Lanabecestat

- Molecular FormulaC26H28N4O

- Average mass412.527 Da

![ChemSpider 2D Image | Lanabecestat | C26H28N4O]()

Dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-[2H]indene-1′(3′H),2”-[2H]imidazol]-4”-amine, 4-methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(1-propyn-1-yl)-3-pyridinyl]-, (1α,1′R,4β)-

(1r,1’R,4R)-4-Methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(1-propin-1-yl)-3-pyridinyl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-indene-1′,2”-imidazol]-4”-amin

(1r,1’R,4R)-4-Methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(1-propyn-1-yl)-3-pyridinyl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-indene-1′,2”-imidazol]-4”-amine

(lr,l’R,4R)- 4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-l-yn-l-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden-l’2′-imidazole]-4″-amine

(lr,4r)-4-Methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane- l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]- “-amine

CAS 1383982-64-6

AZD3293

Dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-[1H]indene-1′(3’H),2”-[2H]imidazol]-4”-amine, 4-methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(1-propyn-1-yl)-3-pyridinyl]-, (1’R)-

Lanabecestat

LY3314814

UNII:X8SPJ492VF, AZ-12304146

Beta amyloid antagonist; Beta secretase 1 inhibitor; Beta secretase 2 inhibitor

Fast Track

- (1α,1’R,4β)-4-Methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(1-propyn-1-yl)-3-pyridinyl]dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-[2H]indene-1′(3’H),2”-[2H]imidazol]-4”-amine

- (1,4-trans,1’R)-4-methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-1-yn-1-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-indene-1′,2”-imidazol]-4”-amine

- (1r,1’R,4R)-4-methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-1-yn-1-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-indene-1′,2”-imidazol]-4”-amine

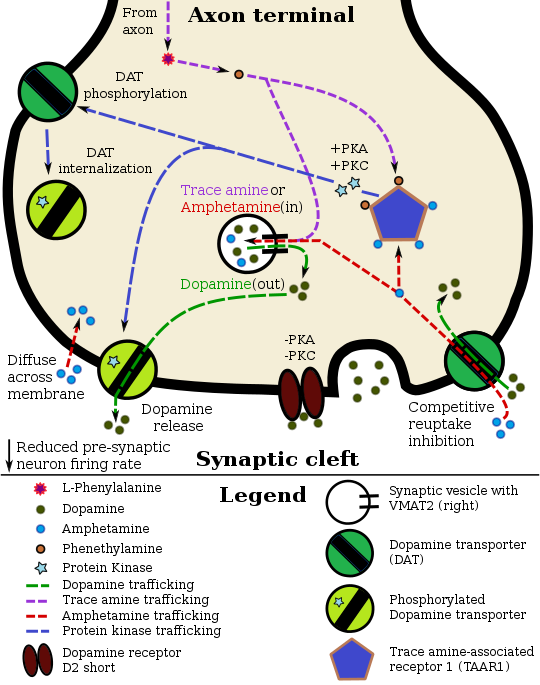

Lanabecestat (formerly known as AZD3293 or LY3314814) is an oral beta-secretase 1 cleaving enzyme (BACE) inhibitor. A BACE inhibitor in theory would prevent the buildup of beta-amyloid and may help slow or stop the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

In September 2014, AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly and Company announced an agreement to co-develop lanabecestat.[1] A pivotal Phase II/III clinical trial of lanabecestat started in late 2014 and is planned to recruit 2,200 patients and end in June 2019.[2] In April 2016 the company announced it would advance to phase 3 without modification.[3]

- Originator Astex Pharmaceuticals; AstraZeneca

- Developer AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly

- Class Antidementias; Imidazoles; Pyridines; Small molecules; Spiro compounds

- Mechanism of Action Amyloid precursor protein secretase inhibitors

- Phase III Alzheimer’s disease

Most Recent Events

- 15 Mar 2017 Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca initiates enrolment in an extension phase III trial for Alzheimer’s Disease (In adults, In the elderly) in USA (PO) (NCT02972658)

- 25 Jan 2017 Chemical structure information added

- 12 Jan 2017 Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca initiate enrolment in a phase I pharmacokinetics trial in Healthy volunteers in USA (PO) (NCT03019549

- Astex Therapeutics Ltd

![Image result]()

![Image result for azd 3293]()

![CHEMBL2152914.png]()

The prime neuropathological event distinguishing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is deposition of the 40-42 residue amyloid β-peptide (Αβ) in brain parenchyma and cerebral vessels. A large body of genetic, biochemical and in vivo data support a pivotal role for Αβ in the pathological cascade that eventually leads to AD. Patients usually present early symptoms (commonly memory loss) in their sixth or seventh decades of life. The disease progresses with increasing dementia and elevated deposition of Αβ. In parallel, a hyperphosphorylated form of the microtubule-associated protein tau accumulates within neurons, leading to a plethora of deleterious effects on neuronal function. The prevailing working hypothesis regarding the temporal relationship between Αβ and tau pathologies states that Αβ deposition precedes tau aggregation in humans and animal models of the disease. Within this context, it is worth noting that the exact molecular nature of Αβ, mediating this pathological function is presently an issue under intense study. Most likely, there is a continuum of toxic species ranging from lower order Αβ oligomers to supramolecular assemblies such as Αβ fibrils. The Αβ peptide is an integral fragment of the Type I protein APP (Αβ amyloid precursor protein), a protein ubiquitously expressed in human tissues. Since soluble Αβ can be found in both plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and in the medium from cultured cells, APP has to undergo proteolysis. There are three main cleavages of APP that are relevant to the pathobiology of AD, the so-called α-, β-, and γ-cleavages. The a-cleavage, which occurs roughly in the middle of the Αβ domain in APP is executed by the metalloproteases AD AMI 0 or AD AMI 7 (the latter also known as TACE). The β-cleavage, occurring at the N terminus of Αβ, is generated by the transmembrane aspartyl protease Beta site APP Cleaving Enzymel (BACE1). The γ-cleavage, generating the Αβ C termini and subsequent release of the peptide, is effected by a multi-subunit aspartyl protease named γ-secretase. ADAM10/17 cleavage followed by γ-secretase cleavage results in the release of the soluble p3 peptide, an N- terminally truncated Αβ fragment that fails to form amyloid deposits in humans. This proteolytic route is commonly referred to as the non-amyloidogenic pathway. Consecutive cleavages by BACE1 and γ-secretase generates the intact Αβ peptide, hence this processing scheme has been termed the amyloidogenic pathway. With this knowledge at hand, it is possible to envision two possible avenues of lowering Αβ production: stimulating non- amyloidogenic processing, or inhibit or modulate amyloidogenic processing. This application focuses on the latter strategy, inhibition or modulation of amyloidogenic processing.

Amyloidogenic plaques and vascular amyloid angiopathy also characterize the brains of patients with Trisomy 21 (Down’s Syndrome), Hereditary Cerebral Hemorrhage with Amyloidosis of the Dutch-type (HCHWA-D), and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Neurofibrillary tangles also occur in other neurodegenerative disorders including dementia- inducing disorders (Varghese, J., et al, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2003, 46, 4625-4630). β-amyloid deposits are predominately an aggregate of AB peptide, which in turn is a product of the proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein (APP). More specifically, AB peptide results from the cleavage of APP at the C-terminus by one or more γ-secretases, and at the N- terminus by B-secretase enzyme (BACE), also known as aspartyl protease or Asp2 or Beta site APP Cleaving Enzyme (BACE), as part of the B-amyloidogenic pathway.

BACE activity is correlated directly to the generation of AB peptide from APP (Sinha, et al, Nature, 1999, 402, 537-540), and studies increasingly indicate that the inhibition of BACE inhibits the production of AB peptide (Roberds, S. L., et al, Human Molecular Genetics, 2001, 10, 1317-1324). BACE is a membrane bound type 1 protein that is

synthesized as a partially active proenzyme, and is abundantly expressed in brain tissue. It is thought to represent the major β-secretase activity, and is considered to be the rate-limiting step in the production of amyloid^-peptide (Αβ).

Drugs that reduce or block BACE activity should therefore reduce Αβ levels and levels of fragments of Αβ in the brain, or elsewhere where Αβ or fragments thereof deposit, and thus slow the formation of amyloid plaques and the progression of AD or other maladies involving deposition of Αβ or fragments thereof. BACE is therefore an important candidate for the development of drugs as a treatment and/or prophylaxis of Αβ-related pathologies such as Down’s syndrome, β-amyloid angiopathy such as but not limited to cerebral amyloid angiopathy or hereditary cerebral hemorrhage, disorders associated with cognitive impairment such as but not limited to MCI (“mild cognitive impairment”), Alzheimer’s Disease, memory loss, attention deficit symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease, neurodegeneration associated with diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia including dementia of mixed vascular and degenerative origin, pre-senile dementia, senile dementia and dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy or cortical basal degeneration.

It would therefore be useful to inhibit the deposition of Αβ and portions thereof by inhibiting BACE through inhibitors such as the compounds provided herein.

The therapeutic potential of inhibiting the deposition of Αβ has motivated many groups to isolate and characterize secretase enzymes and to identify their potential inhibitors.

![]()

SYNTHESIS

![]()

As in WO 2013190302

PATENT

EXAMPLES

Example 1

6′-Bromospiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene]-l’,4(3’H)-dione

![Figure imgf000016_0001]()

Potassium tert-butoxide (223 g, 1.99 mol) was charged to a 100 L reactor containing a stirred mixture of 6-bromo-l-indanone (8.38 kg, 39.7 mol) in THF (16.75 L) at 20-30 °C. Methyl acrylate (2.33 L, 25.8 mol) was then charged to the mixture during 15 minutes keeping the temperature between 20-30 °C. A solution of potassium tert-butoxide (89.1 g, 0.79 mol) dissolved in THF (400 mL) was added were after methyl acrylate (2.33 L, 25.8 mol) was added during 20 minutes at 20-30 °C. A third portion of potassium tert-butoxide (90 g, 0.80 mol) dissolved in THF (400 mL) was then added, followed by a third addition of methyl acrylate (2.33 L, 25.8 mol) during 20 minutes at 20-30 °C. Potassium tert-butoxide (4.86 kg, 43.3 mol) dissolved in THF (21.9 L) was charged to the reactor during 1 hour at 20-30 °C. The reaction was heated to approximately 65 °C and 23 L of solvent was distilled off. Reaction temperature was lowered to 60 °C and 50% aqueous potassium hydroxide (2.42 L, 31.7 mol) dissolved in water (51.1 L) was added to the mixture during 30 minutes at 55-60 °C were after the mixture was stirred for 6 hours at 60 °C, cooled to 20 °C during 2 hours. After stirring for 12 hours at 20 °C the solid material was filtered off, washed twice with a mixture of water (8.4 L) and THF (4.2 L) and then dried at 50 °C under vacuum to yield 6′- bromospiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene]-r,4(3’H)-dione (7.78 kg; 26.6 mol). 1H MR (500 MHz, DMSO-i¾) δ ppm 1.78 – 1.84 (m, 2 H), 1.95 (td, 2 H), 2.32 – 2.38 (m, 2 H), 2.51 – 2.59 (m, 2 H), 3.27 (s, 2 H), 7.60 (d, 1 H), 7.81 (m, 1 H), 7.89 (m, 1 H).

Example 2

(lr,4r)-6′-Bromo-4-methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]-l'(3’H)-one

![Figure imgf000016_0002]()

Borane tert-butylamine complex (845 g, 9.7 mol) dissolved in DCM (3.8 L) was charged to a slurry of 6′-Bromospiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene]- ,4(3’H)-dione (7.7 kg, 26.3 mol) in DCM (42.4 L) at approximately 0-5 °C over approximately 25 minutes. The reaction was left with stirring at 0-5°C for 1 hour were after analysis confirmed that the conversion was >98%. A solution prepared from sodium chloride (2.77 kg), water (13.3 L) and 37% hydrochloric acid (2.61 L, 32 mol) was charged. The mixture was warmed to approximately 15 °C and the phases separated after settling into layers. The organic phase was returned to the reactor, together with methyl methanesulfonate (2.68 L, 31.6 mol) and tetrabutylammonium chloride (131 g, 0.47 mol) and the mixture was vigorously agitated at 20 °C. 50% Sodium hydroxide (12.5 L, 236 mol) was then charged to the vigorously agitated reaction mixture over approximately 1 hour and the reaction was left with vigorously agitation overnight at 20 °C. Water (19 L) was added and the aqueous phase discarded after separation. The organic layer was heated to approximately 40 °C and 33 L of solvent were distilled off. Ethanol (21 L) was charged and the distillation resumed with increasing temperature (22 L distilled off at up to 79 °C). Ethanol (13.9 L) was charged at approximately 75 °C. Water (14.6 L) was charged over 30 minutes keeping the temperature between 72-75 °C. Approximately 400 mL of the solution is withdrawn to a 500 mL polythene bottle and the sample crystallised spontaneously. The batch was cooled to 50 °C were the crystallised slurry sample was added back to the solution. The mixture was cooled to 40 °C. The mixture was cooled to 20 °C during 4 hours were after it was stirred overnight. The solid was filtered off , washed with a mixture of ethanol (6.6 L) and water (5 L) and dried at 50 °C under vacuum to yield (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4- methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]-r(3’H)-one (5.83 kg, 18.9 mol) 1H MR (500 MHz,

DMSO-i¾) δ ppm 1.22-1.32 (m, 2 H), 1.41 – 1.48 (m, 2 H), 1.56 (td, 2 H), 1.99 – 2.07 (m, 2 H), 3.01 (s, 2 H), 3.16 – 3.23 (m, 1 H), 3.27 (s, 3 H), 7.56 (d, 1 H), 7.77 (d, 1 H), 7.86 (dd, 1

H).

Example 3

(lr,4r)-6′-Bromo-4-methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]-l'(3’H)-imine hydrochloride

![Figure imgf000017_0001]()

(lr,4r)-6′-Bromo-4-methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]- (3’H)-one (5.82 kg; 17.7 mol) was charged to a 100 L reactor at ambient temperature followed by titanium (IV)ethoxide (7.4 L; 35.4 mol) and a solution of tert-butylsulfinamide (2.94 kg; 23.0 mol) in 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (13.7 L). The mixture was stirred and heated to 82 °C. After 30 minutes at 82 °C the temperature was increased further (up to 97 °C) and 8 L of solvent was distilled off. The reaction was cooled to 87 °C and 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (8.2 L) was added giving a reaction temperature of 82 °C. The reaction was left with stirring at 82 °C overnight. The reaction temperature was raised (to 97 °C) and 8.5 L of solvent was distilled off. The reaction was cooled down to 87 °C and 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (8.2 L) was added giving a reaction temperature of 82 °C. After 3.5 hours the reaction temperature was increased further (to 97 °C) and 8 L of solvent was distilled off. The reaction was cooled to 87 °C and 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (8.2 L) was added giving a reaction temperature of 82 °C. After 2 hours the reaction temperature was increased further (to 97 °C) and 8.2 L of solvent was distilled off. The reaction was cooled to 87 °C and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (8.2 L) was added giving a reaction temperature of 82 °C. The reaction was stirred overnight at 82 °C. The reaction temperature was increased further (to 97 °C) and 8 L of solvent was distilled off. The reaction was cooled down to 25 °C. Dichloromethane (16.4 L) was charged. To a separate reactor water (30 L) was added and agitated vigorously and sodium sulfate (7.54 kg) was added and the resulting solution was cooled to 10 °C. Sulfuric acid (2.3 L, 42.4 mol) was added to the water solution and the temperature was adjusted to 20 °C. 6 L of the acidic water solution was withdrawn and saved for later. The organic reaction mixture was charged to the acidic water solution over 5 minutes with good agitation. The organic reaction vessel was washed with dichloromethane (16.4 L), and the dichloromethane wash solution was also added to the acidic water. The mixture was stirred for 15 minutes and then allowed to settle for 20 minutes. The lower aqueous phase was run off, and the saved 6 L of acidic wash was added followed by water (5.5 L). The mixture was stirred for 15 minutes and then allowed to settle for 20 minutes. The lower organic layer was run off to carboys and the upper water layer was discarded. The organic layer was charged back to the vessel followed by sodium sulfate (2.74 kg), and the mixture was agitated for 30 minutes. The sodium sulfate was filtered off and washed with dichloromethane (5.5 L) and the combined organic phases were charged to a clean vessel. The batch was heated for distillation (collected 31 L max temperature 57 °C). The batch was cooled to 40 °C and dichloromethane (16.4 L) was added. The batch was heated for distillation (collected 17 L max temperature 54 °C). The batch was cooled to 20 °C and dichloromethane (5.5 L) and ethanol (2.7 L) were. 2 M hydrogen chloride in diethyl ether (10.6 L; 21.2 mol) was charged to the reaction over 45 minutes keeping the temperature between 16-23 °C. The resulting slurry was stirred at 20 °C for 1 hour whereafter the solid was filtered off and washed 3 times with a 1 : 1 mixture of dichloromethane and diethyl ether (3 x 5.5 L). The solid was dried at 50 °C under vacuum to yield (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4- methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]-l'(3’H)-imine hydrochloride (6.0 kg; 14.3 mol; assay 82% w/w by 1H MR) 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-i¾) δ ppm 130 (m, 2 H), 1.70 (d, 2 H), 1.98 (m, 2 H), 2.10 (m, 2 H), 3.17 (s, 2 H), 3.23 (m, 1 H), 3.29 (s, 3 H), 7.61 (d, 1 H), 8.04 (dd, 1 H), 8.75 (d, 1 H), 12.90(br s,2H).

Example 4

(lr,4r)-6′-Bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden-l’2′- imidazole]-4″ (3″H)-thione

![Figure imgf000019_0001]()

Trimethylorthoformate (4.95 L; 45.2 mol) and diisopropylethylamine (3.5 L; 20.0 mol) was charged to a reactor containing (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4-methoxyspiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden]- l'(3’H)-imine hydrochloride (6.25 kg; 14.9 mol) in isopropanol (50.5 L). The reaction mixture was stirred and heated to 75 °C during 1 hour so that a clear solution was obtained. The temperature was set to 70 °C and a 2 M solution of 2-oxopropanethioamide in isopropanol (19.5 kg; 40.6 mol) was charged over 1 hour, were after the reaction was stirred overnight at 69 °C. The batch was seeded with (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]-4″(3″H)-thione (3 g ; 7.6 mmol) and the temperature was lowered to 60 °C and stirred for 1 hour. The mixture was concentrated by distillation (distillation temperature approximately 60 °C; 31 L distilled off). Water (31 L) was added during 1 hour and 60 °C before the temperature was lowered to 25 °C during 90 minutes were after the mixture was stirred for 3 hours. The solid was filtered off , washed with isopropanol twice (2 x 5.2 L) and dried under vacuum at 40 °C to yield (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4- methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]-4″(3″H)-thione (4.87 kg; 10.8 mol; assay of 87% w/w by 1H NMR). Example 5

(lr,l’R,4R)-6′-Bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden-l’2′- imidazole]-4″-amine D(+)-10-Camphorsulfonic acid salt

![Figure imgf000020_0001]()

7 M Ammonia in methanol (32 L; 224 mol) was charged to a reactor containing (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4-methoxy-5”-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]- 4″(3″H)-thione (5.10 kg; 11.4 mol) and zinc acetate dihydrate (3.02 kg ; 13.8 mol). The reactor was sealed and the mixture was heated to 80 °C and stirred for 24 hours, were after it was cooled to 30 °C. 1-Butanol (51L) was charged and the reaction mixture was concentrated by vacuum distilling off approximately 50 L. 1-Butanol (25 L) was added and the mixture was concentrated by vacuum distilling of 27 L. The mixture was cooled to 30 °C and 1 M sodium hydroxide (30 L; 30 mol) was charged. The biphasic mixture was agitated for 15 minutes. The lower aqueous phase was separated off. Water (20 L) was charged and the mixture was agitated for 30 minutes. The lower aqueous phase was separated off. The organic phase was heated to 70 °C were after (l S)-(+)-10-camphorsulfonic acid (2.4 kg; 10.3 mol) was charged. The mixture was stirred for 1 hour at 70 °C and then ramped down to 20 °C over 3 hours. The solid was filtered off, washed with ethanol (20 L) and dried in vacuum at 50 °C to yield (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]- 4″-amine (+)-10-Camphor sulfonic acid salt (3.12 kg; 5.13 mol; assay 102%w/w by 1H

MR).

Example 6

(lr,l’R,4R)- 4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-l-yn-l-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden-l’2′-imidazole]-4″-amine

Na2PdCl4 (1.4 g; 4.76 mmol) and 3-(di-tert-butylphosphonium)propane sulfonate (2.6 g; 9.69 mmol) dissolved in water (0.1 L) was charged to a vessel containing (lr,4r)-6′-bromo- 4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]-4″-amine (+)-10- camphorsulfonic acid salt (1 kg; 1.58 mol), potassium carbonate (0.763 kg; 5.52 mol) in a mixture of 1-butanol (7.7 L) and water (2.6 L). The mixture is carefully inerted with nitrogen whereafter 5-(prop-l-ynyl)pyridine-3-yl boronic acid (0.29 kg; 1.62 mol) is charged and the mixture is again carefully inerted with nitrogen. The reaction mixture is heated to 75 °C and stirred for 2 hours were after analysis showed full conversion. Temperature was adjusted to 45 °C. Stirring was stopped and the lower aqueous phase was separated off. The organic layer was washed 3 times with water (3 x 4 L). The reaction temperature was adjusted to 22 °C and Phosphonics SPM32 scavenger (0.195 kg) was charged and the mixture was agitated overnight. The scavenger was filtered off and washed with 1-butanol (1 L). The reaction is concentrated by distillation under reduced pressure to 3 L. Butyl acetate (7.7 L) is charged and the mixture is again concentrated down to 3 L by distillation under reduced pressure. Butyl acetate (4.8 L) was charged and the mixture was heated to 60 °C. The mixture was stirred for 1 hour were after it was concentrated down to approximately 4 L by distillation under reduced pressure. The temperature was set to 60 °C and heptanes (3.8 L) was added over 20 minutes. The mixture was cooled down to 20 °C over 3 hours and then left with stirring overnight. The solid was filtered off and washed twice with a 1 : 1 mixture of butyl acetate: heptane (2 x 2 L). The product was dried under vacuum at 50 °C to yield (lr, R,4R)-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′- [5-(prop-l-yn-l-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2′-imidazole]-4”- amine (0.562 kg; 1.36 mol; assay 100% w/w by 1H MR). 1H MR (500 MHz, DMSO-i¾) δ ppm 0.97 (d, 1 H), 1.12-1.30 (m, 2 H), 1.37-1.51 (m, 3 H), 1.83 (d, 2 H), 2.09 (s, 3 H), 2.17 (s, 2 H), 2.89-3.12 (m, 3 H), 3.20 (s, 3 H), 6.54 (s, 2 H), 6.83 (s, 1 H), 7.40 (d, 1 H), 7.54 (d, 1 H), 7.90(s,lH). 8.51(d,lH), 8.67(d, lH)

Example 7

Preparation of camsylate salt of (lr,l’R,4R)- 4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-l-yn-l- yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden-l’2′-imidazole]-4′ ‘-amine

1.105 kg (lr, l ‘R,4R)- 4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-l-yn-l-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- 2’-imidazole]-4″-amine was dissolved in 8.10 L 2-propanol and 475 mL water at 60 °C. Then 1.0 mole equivalent (622 gram) (l S)-(+)-10

camphorsulfonic acid was charged at 60 °C. The slurry was agitated until all (l S)-(+)-10 camphorsulfonic acid was dissolved. A second portion of 2-propanol was added (6.0 L) at 60 °C and then the contents were distilled until 4.3 L distillate was collected. Then 9.1 L Heptane was charged at 65 °C. After a delay of one hour the batch became opaque. Then an additional distillation was performed at about 75 °C and 8.2 L distillate was collected. The batch was then cooled to 20 °C over 2 hrs and held at that temperature overnight. Then the batch was filtered and washed with a mixture of 1.8 L 2-propanol and 2.7 L heptane. Finally the substance was dried at reduced pressure and 50 °C. The yield was 1.44 kg (83.6 % w/w). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.12 (1H, s), 9,70 (2H, d, J 40.2), 8.81 (1H, d, J2.1), 8.55 (1H, d, J 1.7), 8.05 (1H, dd, J2.1, 1.7), 7.77 (1H, dd, J7.8, 1.2), 7.50 (2H, m), 3.22 (3H, s), 3.19 (1H, d, J 16.1), 3.10 (1H, d, J 16.1), 3.02 (1H, m), 2.90 (1H, d, J 14.7), 2.60 (1H, m), 2.41 (1H, d, J 14.7), 2.40 (3H, s), 2.22 (1H, m), 2.10 (3H, s), 1.91 (3H, m), 1.81 (1H, m), 1.77 (1H, d, J 18.1), 1.50 (2H, m), 1.25 (6H, m), 0.98 (3H, s), 0.69 (3H, s).

![str1]()

PATENT

WO 2012087237

| Inventors |

Gabor Csjernyik, Sofia KARLSTRÖM, Annika Kers, Karin Kolmodin, Martin Nylöf, Liselotte ÖHBERG, Laszlo Rakos, Lars Sandberg, Fernando Sehgelmeble, Peter SÖDERMAN, Britt-Marie Swahn, Berg Stefan Von, Less « |

| Applicant |

Astrazeneca Ab |

Example 20a (lr,4r)-4-Methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane- l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]- “-amine

Method A

5-(Prop-l-ynyl)pyridin-3-ylboronic acid (Intermediate 15, 0.044 g, 0.27 mmol), (lr,4r)-6′- bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene- ,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (Example 19 Method A Step 4, 0.085 g, 0.23 mmol), [l, l’-bis(diphenylphosphino)- ferrocene]palladium(II) chloride (9.29 mg, 0.01 mmol), K2C03 (2M aq., 1.355 mL, 0.68 mmol) and 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran (0.5 mL) were mixed and heated to 100 °C using MW for 2×30 min. 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran (5 mL) and H20 (5 mL) were added and the layers were separated. The organic layer was dried with MgS04 and then concentrated. The crude was dissolved in DCM and washed with H20. The organic phase was separated through a phase separator and dried in vacuo. The crude product was purified with preparative chromatography. The solvent was evaporated and the H20-phase was extracted with DCM. The organic phase was separated through a phase separator and dried to give the title compound (0.033 g, 36% yield), 1H MR (500 MHz, CD3CN) δ ppm 1.04 – 1.13 (m, 1 H), 1.23 – 1.35 (m, 2 H), 1.44 (td, 1 H), 1.50 – 1.58 (m, 2 H), 1.84 – 1.91 (m, 2 H), 2.07 (s, 3 H), 2.20 (s, 3 H), 3.00 (ddd, 1 H), 3.08 (d, 1 H), 3.16 (d, 1 H), 3.25 (s, 3 H), 5.25 (br. s., 2 H), 6.88 (d, 1 H), 7.39 (d, 1 H), 7.49 (dd, 1 H), 7.85 (t, 1 H), 8.48 (d, 1 H), 8.64 (d, 1 H), MS (MM-ES+APCI)+w/z 413 [M+H]+.

Separation of the isomers of (lr,4r)-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3- yl)-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine

(lr,4r)-4-Methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′- indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (Example 20a, 0.144 g, 0.35 mmol) was purified using preparative chromatography (SFC Berger Multigram II, Column: Chiralcel OD-H; 20*250 mm; 5μιη, mobile phase: 30% MeOH (containing 0.1% DEA); 70% C02, Flow: 50 mL/min, total number of injections: 4). Fractions which contained the product were combined and the MeOH was evaporated to give: Isomer 1: (lr, R,4R)-4-methoxy-5”-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H-dispiro- [cyclohexane-l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (49 mg, 34% yield) with retention time 2.5 min:

![Figure imgf000118_0001]()

1H MR (500 MHz, CD3CN) δ ppm 1.07 – 1.17 (m, 1 H), 1.23 – 1.39 (m, 2 H), 1.47 (td, 1 H), 1.57 (ddq, 2 H), 1.86 – 1.94 (m, 2 H), 2.09 (s, 3 H), 2.23 (s, 3 H), 2.98 – 3.07 (m, 1 H), 3.11 (d, 1 H), 3.20 (d, 1 H), 3.28 (s, 3 H), 5.30 (br. s., 2 H), 6.91 (d, 1 H), 7.42 (d, 1 H), 7.52 (dd, 1 H), 7.88 (t, 1 H), 8.51 (d, 1 H), 8.67 (d, 1 H), MS (MM-ES+APCI)+ m/z 413.2 [M+H]+; and

Isomer 2: (lr,l’S,4S)-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (50 mg, 35% yield) with retention time 6.6 min:

1H MR (500 MHz, CD3CN) δ ppm 1.02 – 1.13 (m, 1 H), 1.20 – 1.35 (m, 2 H), 1.44 (d, 1 H), 1.54 (ddd, 2 H), 1.84 – 1.91 (m, 2 H), 2.06 (s, 3 H), 2.20 (s, 3 H), 3.00 (tt, 1 H), 3.08 (d, 1 H), 3.16 (d, 1 H), 3.25 (s, 3 H), 5.26 (br. s., 2 H), 6.88 (d, 1 H), 7.39 (d, 1 H), 7.49 (dd, 1 H), 7.84 (t, 1 H), 8.48 (d, 1 H), 8.63 (d, 1 H), MS (MM-ES+APCI)+ m/z 413.2 [M+H]+.

Method B

A vessel was charged with (lr,4r)-6′-bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H-dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′- indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (Example 19 Method B Step 4, 7.5 g, 19.9 mmol), 5-(prop-l- ynyl)pyridin-3-ylboronic acid (Intermediate 15, 3.37 g, 20.9 mmol), 2.0 M aq. K2C03 (29.9 mL, 59.8 mmol), and 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran (40 mL). The vessel was purged under vacuum and the atmosphere was replaced with argon. Sodium tetrachloropalladate (II) (0.147 g, 0.50 mmol) and 3-(di-tert-butyl phosphonium) propane sulfonate (0.267 g, 1.00 mmol) were added and the contents were heated to reflux for a period of 16 h. The contents were cooled to 30 °C and the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran (2 x 10 mL), then the organics were combined, washed with brine and treated with activated charcoal (2.0 g). The mixture was filtered over diatomaceous earth, and then washed with 2-methyl- tetrahydrofuran (20 mL). The filtrate was concentrated to a volume of approximately 50 mL, then water (300 μL) was added, and the contents were stirred vigorously as seed material was added to promote crystallization. The product began to crystallize and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at r.t., then 30 min. at 0-5 °C in an ice bath before being filtered. The filter cake was washed with 10 mL cold 2-methyl-tetrahydrofuran and then dried in the vacuum oven at 45 °C to give the racemic title compound (5.2 g, 12.6 mmol, 63% yield): MS (ES+) m/z 413 [M+H]+.

(lr,l’R,4R)-4-Methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-l-yn-l-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3’H-dispiro- [cyclohexane-l,2′-indene-l’ “-imidazol]-4”-amine (isomer 1)

Method C

A solution of (lr,4r)-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-6′-(5-prop-l-yn-l-ylpyridin-3-yl)-3’H-dispiro- [cyclohexane-l,2′-indene-l’,2″-imidazol]-4″-amine (Example 20a method B, 4.85 g, 11.76 mmol) and EtOH (75 mL) was stirred at 55 °C. A solution of (+)-di-p-toluoyl-D-tartaric acid (2.271 g, 5.88 mmol) in EtOH (20 mL) was added and stirring continued. After 2 min. a precipitate began to form. The mixture was stirred for 2 h before being slowly cooled to 30 °C and then stirred for a further 16 h. The heat was removed and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 30 min. The mixture was filtered and the filter cake washed with chilled EtOH (45 mL). The solid was dried in the vacuum oven at 45 °C for 5 h, then the material was charged to a vessel and DCM (50 mL) and 2.0 M aq. NaOH solution (20 mL) were added. The mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 15 min. The phases were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with 10 mL DCM. The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo to a residue and 20 mL EtOH was added. The resulting solution was stirred at r.t. as water (15 mL) was slowly added to the vessel. A precipitate slowly began to form, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 10 min. before additional water (20 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h and then filtered. The filter cake was washed with water (15 mL) and dried in a vacuum oven at 45 °C for a period of 16 h to give the title compound (1.78 g, 36% yield): MS (ES+) m/z 413 [M+H]+. This material is equivalent to Example 20a Isomer 1 above. Method D

To a 500 mL round-bottomed flask was added (lr, R,4R)-6′-bromo-4-methoxy-5″-methyl-3’H- dispiro[cyclohexane-l,2′-inden- ,2′-imidazole]-4″-amine as the D(+)-10-camphor sulfonic acid salt (Example 19 Method B Step 5, 25.4 g, 41.7 mmol), 2 M aq. KOH (100 mL) and 2-methyl- tetrahydrofuran (150 mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 min at r.t. after which the mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel and allowed to settle. The phases were separated and the organic phase was washed with 2 M aq. K2C03 (100 mL). The organic phase was transferred to a 500 mL round-bottomed flask followed by addition of 5-(prop-l-ynyl)pyridin-3-ylboronic acid (Intermediate 15, 6.72 g, 41.74 mmol), K2C03 (2.0 M, 62.6 mL, 125.21 mmol). The mixture was degassed by means of bubbling Ar through the solution for 5 min. To the mixture was then added sodium tetrachloropalladate(II) (0.307 g, 1.04 mmol) and 3-(di-tert- butylphosphonium)propane sulfonate (0.560 g, 2.09 mmol) followed by heating the mixture at reflux (80 °C) overnight. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool down to r.t. and the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with 2-Me-THF (2×100 mL). The organics were combined, washed with brine and treated with activated charcoal. The mixture was filtered over diatomaceous earth and the filter cake was washed with 2-Me-THF (2×20 mL), and the filtrate was concentrated to give 17.7 g that was combined with 2.8 g from other runs. The material was dissolved in 2-Me-THF under warming and put on silica (-500 g). Elution with 2- Me-THF/ Et3N (100:0-97.5:2.5) gave the product. The solvent was evaporated, then co- evaporated with EtOH (absolute, 250 mL) to give (9.1 g, 53% yield). The HCl-salt was prepared to purify the product further: The product was dissolved in CH2C12 (125 mL) under gentle warming, HC1 in Et20 (-15 mL) in Et20 (100 mL) was added, followed by addition of Et20 (-300 mL) to give a precipitate that was filtered off and washed with Et20 to give the HCl-salt. CH2C12 and 2 M aq. NaOH were added and the phases separated. The organic phase was concentrated and then co-evaporated with MeOH. The formed solid was dried in a vacuum cabinet at 45 °C overnight to give the title compound (7.4 g, 43% yield): 1H MR (500 MHz, DMSO-i¾) δ ppm 0.97 (d, 1 H) 1.12 – 1.30 (m, 2 H) 1.37 – 1.51 (m, 3 H) 1.83 (d, 2 H) 2.09 (s, 3 H) 2.17 (s, 3 H) 2.89 – 3.12 (m, 3 H) 3.20 (s, 3 H) 6.54 (s, 2 H) 6.83 (s, 1 H) 7.40 (d, 1 H) 7.54 (d, 1 H) 7.90 (s, 1 H) 8.51 (d, 1 H) 8.67 (d, 1 H); HRMS-TOF (ES+) m/z 413.2338 [M+H]+ (calculated 413.2341); enantiomeric purity >99.5%; NMR Strength 97.8±0.6% (not including water).

References

- Jump up^ “AstraZeneca and Lilly announce alliance to develop and commercialise BACE inhibitor AZD3293 for Alzheimer’s disease”. http://www.astrazeneca.com. 16 Sep 2014. Retrieved 8 Oct 2014.

- Jump up^ “AstraZeneca and Lilly move Alzheimer’s drug into big trial”. December 2014.

- Jump up^ Lilly and AstraZeneca Alzheimer’s candidate advances; AstraZeneca earns $100M milestone. April 2016

| Cited Patent |

Filing date |

Publication date |

Applicant |

Title |

| WO2011002408A1 * |

Jul 2, 2010 |

Jan 6, 2011 |

Astrazeneca Ab |

Novel compounds for treatment of neurodegeneration associated with diseases, such as alzheimer’s disease or dementia |

| WO2012087237A1 * |

Dec 21, 2011 |

Jun 28, 2012 |

Astrazeneca Ab |

Compounds and their use as bace inhibitors |

| Reference |

| 1 |

|

BUNN, C. W.: “Chemical Crystallography“, 1948, CLARENDON PRESS |

| 2 |

|

GIACOVAZZO, C. ET AL.: “Fundamentals of Crystallography“, 1995, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS |

| 3 |

|

JENKINS, R.; SNYDER, R. L.: “ntroduction to X-Ray Powder Diffractometry“, 1996, JOHN WILEY & SONS |

| 4 |

|

KLUG, H. P.; ALEXANDER, L. E.: “X-ray Diffraction Procedures“, 1974, JOHN WILEY AND SONS |

| 5 |

|

ROBERDS, S. L. ET AL., HUMAN MOLECULAR GENETICS, vol. 10, 2001, pages 1317 – 1324 |

| 6 |

|

SINHA ET AL., NATURE, vol. 402, 1999, pages 537 – 540 |

| 7 |

|

VARGHESE, J. ET AL., JOURNAL OF MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY, vol. 46, 2003, pages 4625 – 4630 |

| Patent ID |

Patent Title |

Submitted Date |

Granted Date |

| US8865911 |

Compounds and their use as BACE inhibitors |

2013-03-15 |

2014-10-21 |

| US8415483 |

Compounds and their use as BACE inhibitors |

2011-12-20 |

2013-04-09 |

| US2015133471 |

COMPOUNDS AND THEIR USE AS BACE INHIBITORS |

2014-09-15 |

2015-05-14 |

| US2016184303 |

COMPOUNDS AND THEIR USE AS BACE INHIBITORS |

2015-12-22 |

2016-06-30 |

Lanabecestat

![Lanabecestat.svg]() |

| Names |

Systematic IUPAC name

4-Methoxy-5′′-methyl-6′-[5-(prop-1-yn-1-yl)pyridin-3-yl]-3′H-dispiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-indene-1′,2′′-imidazole]-4′′-amine

|

| Other names

AZD3293; LY3314814

|

| Identifiers |

|

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

|

|

|

| Properties |

|

|

C26H28N4O |

| Molar mass |

412.54 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

CC#CC1=CC(=CN=C1)C2=CC3=C(CC4(C35N=C(C(=N5)N)C)CCC(CC4)OC)C=C2

PAPER

![]()

![Figure]()

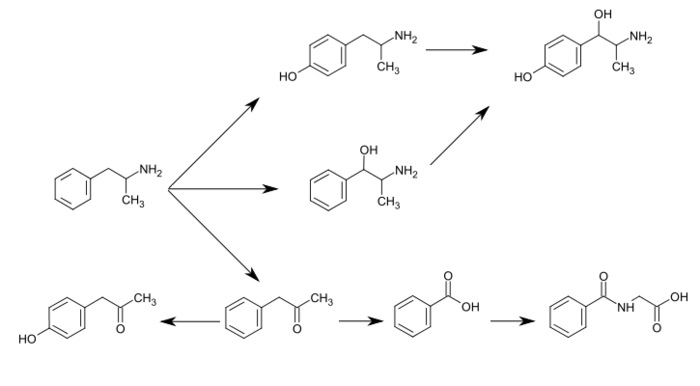

Structure of Eli Lilly/AstraZeneca BACE1 inhibitor AZD3292 (+)-camsylate and of the 3-propynylpyridine fragment common to several BACE1 inhibitors.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease resulting in personality and behavioral disturbances, impaired memory loss, inability to perform daily tasks, and death.(1) AD affects an estimated 47 million patients and their families worldwide,(2) and this number is expected to rise to 115 million by 2050.(3) AD is caused through the accumulation of β-amyloid proteins into plaques outside neurons in the brain.(4) It is thought that soluble forms of this protein are neurotoxic and are the main cause of deterioration seen in Alzheimer patients. The soluble protein fragments are made through the cutting of larger proteins, namely, amyloid precursor protein (APP), by two enzymes: β-site amyloid cleaving enzyme (BACE) and γ-secretase. Notably, BACE1 inhibitors have shown promise as potentially disease-modifying treatments for AD.(5) The novel, potent BACE-1 inhibitor AZD3293 (LY3314814) is a brain-permeable, orally active compound with a slow off-rate from its target enzyme, BACE1, which robustly reduced plasma, CSF, and brain Aβ40, Aβ42, and sAβPPβ concentrations in multiple nonclinical species, in elderly subjects, and patients with AD. Eli Lilly and Co. and AstraZeneca are currently studying AZD3293 in phase 3 clinical trials.

Development of a Continuous-Flow Sonogashira Cross-Coupling Protocol using Propyne Gas under Process Intensified Conditions

† Institute of Chemistry, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Heinrichstrasse 28, 8010 Graz, Austria

‡ Research Center Pharmaceutical Engineering GmbH (RCPE), Inffeldgasse 13, 8010 Graz, Austria

§ AstraZeneca, Silk Road Business Park, Macclesfield SK10 2NA, United Kingdom

Org. Process Res. Dev., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00160

Abstract

The development of a continuous-flow Sonogashira cross-coupling protocol using propyne gas for the synthesis of a key intermediate in the manufacturing of a β-amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) inhibitor, currently undergoing late stage clinical trials for a disease-modifying therapy of Alzheimer’s disease, is described. Instead of the currently used batch manufacturing process for this intermediate that utilizes TMS-propyne as reagent, we herein demonstrate the safe utilization of propyne gas, as a cheaper and more atom efficient reagent, using an intensified continuous-flow protocol under homogeneous conditions. The flow process afforded the target intermediate with a desired product selectivity of ∼91% (vs the bis adduct) after a residence time of 10 min at 160 °C. The continuous-flow process compares favorably with the batch process, which uses TMS-propyne and requires overnight processing, TBAF as an additive, and a significantly higher loading of Cu co-catalyst.

Product 3:

![]()

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 8.48 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.00 (s, 3H).

![]()

13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 150.2, 149.0, 140.7, 122.5, 119.9, 91.2, 75.2, 4.4.

![]()

Product 6: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 8.47 (d, J = 1.9, 2H), 7.63 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H) 2.08 (s, 6H).

Product 4 was isolated for NMR analysis using the same purification procedure as described for product 3.

1 H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 8.54 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.42 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.65–1.40 (m, 4H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H).

![]()

13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ ppm 150.5, 149.2, 140.9, 122.8, 120.1, 95.9, 76.2, 30.6, 22.1, 19.3, 13.7.

![]()

![str1]()

![str2]()

![str3]()

![str4]()

![str5]()

![str6]()

///////////////Lanabecestat, LY3314814, 1383982-64-6, AZD3293, PHASE 3, AZ-12304146, Fast Track, Nootropic agent, Neuroprotectant

EX Principal Investigator,

EX Principal Investigator,