Trofinetide

- Molecular FormulaC13H21N3O6

- Average mass315.322 Da

Tofinetide , NNZ-256610076853400-76-7[RN]

glycyl-2-methyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

H-Gly-PMe-Glu-OHL-Glutamic acid, glycyl-2-methyl-L-prolyl-UNII-Z2ME8F52QLZ2ME8F52QLтрофинетид [Russian] [INN]تروفينيتيد [Arabic] [INN]曲非奈肽 [Chinese] [INN]

| IUPAC Condensed | H-Gly-aMePro-Glu-OH |

|---|---|

| Sequence | GXE |

| HELM | PEPTIDE1{G.[*C(=O)[C@@]1(CCCN1*)C |$_R2;;;;;;;;_R1;$|].E}$$$$ |

| IUPAC | glycyl-alpha-methyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid |

An (1-3) IGF-1 analog with neuroprotective activity.

OPTICAL ROT; -52.4 ° Conc: 0.19 g/100mL; water ; 589.3 nm; Temp: 20 °C; Len: 1.0 dm…Tetrahedron 2005, V61(42), P10018-10035

EU Customs Code CN, 29339980

Harmonized Tariff Code, 293399

- L-Glutamic acid, glycyl-2-methyl-L-prolyl-

- glycyl-2-methyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

- Glycyl-L-2-methylprolyl-L-glutamic acid

Trofinetide (NNZ-2566) is a drug developed by Neuren Pharmaceuticals that acts as an analogue of the neuropeptide (1-3) IGF-1, which is a simple tripeptide with sequence Gly–Pro–Glu formed by enzymatic cleavage of the growth factor IGF-1 within the brain. Trofinetide has anti-inflammatory properties and was originally developed as a potential treatment for stroke,[1][2] but has subsequently been developed for other applications and is now in Phase II clinical trials against Fragile X syndrome and Rett syndrome.[3][4][5]

Trofinetide (NNZ-2566), a neuroprotective analogue of glypromate, is a novel molecule that has a profile suitable for both intravenous infusion and chronic oral delivery. It is currently in development to treat traumatic brain injury.

In February 2021, Neuren is developing trofinetide (NNZ-2566, phase 2 clinical ), a small-molecule analog of the naturally occurring neuroprotectant and N-terminus IGF-1 tripeptide Glypromate (glycine-proline-glutamate), for intravenous infusion treatment of various neurological conditions, including moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, chronic neurodegenerative disorders and peripheral neuropathies. At the same time, Neuren is also investigating an oral formulation of trofinetide (phase 3 clinical) for similar neurological indications, including mild TBI.

Autism Spectrum Disorders and neurodevelopment disorders (NDDs) are becoming increasingly diagnosed. According to the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual oƒ Mental Disorders (DSM-4), Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a collection of linked developmental disorders, characterized by abnormalities in social interaction and communication, restricted interests and repetitive behaviours. Current classification of ASD according to the DSM-4 recognises five distinct forms: classical autism or Autistic Disorder, Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). A sixth syndrome, pathological demand avoidance (PDA), is a further specific pervasive developmental disorder.

More recently, the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual oƒ Mental Disorders (DSM-5) recognizes recognises Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) as ASDs.

This invention applies to treatment of disorders, regardless of their classification as either DSM-4 or DSM-5.

Neurodevelopment Disorders (NDDs) include Fragile X Syndrome (FXS), Angelman Syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, Phelan McDermid Syndrome, Rett Syndrome, CDKL5 mutations (which also are associated with Rett Syndrome and X-Linked Infantile Spasm Disorder) and others. Many but not all NDDs are caused by genetic mutations and, as such, are sometimes referred to as monogenic disorders. Some patients with NDDs exhibit behaviors and symptoms of autism.

As an example of a NDD, Fragile X Syndrome is an X-linked genetic disorder in which affected individuals are intellectually handicapped to varying degrees and display a variety of associated psychiatric symptoms. Clinically, Fragile X Syndrome is characterized by intellectual handicap, hyperactivity and attentional problems, autism spectrum symptoms, emotional lability and epilepsy (Hagerman, 1997a). The epilepsy seen in Fragile X Syndrome is most commonly present in childhood, but then gradually remits towards adulthood. Hyperactivity is present in approximately 80 percent of affected males (Hagerman, 1997b). Physical features such as prominent ears and jaw and hyper-extensibility of joints are frequently present but are not diagnostic. Intellectual handicap is the most common feature defining the phenotype. Generally, males are more severely affected than females. Early impressions that females are unaffected have been replaced by an understanding of the presence of specific learning difficulties and other neuropsychiatric features in females. The learning disability present in males becomes more defined with age, although this longitudinal effect is more likely a reflection of a flattening of developmental trajectories rather than an explicit neurodegenerative process.

The compromise of brain function seen in Fragile X Syndrome is paralleled by changes in brain structure in humans. MRI scanning studies reveal that Fragile X Syndrome is associated with larger brain volumes than would be expected in matched controls and that this change correlates with trinucleotide expansion in the FMRP promoter region (Jakala et al, 1997). At the microscopic level, humans with Fragile X Syndrome show abnormalities of neuronal dendritic structure, in particular, an abnormally high number of immature dendritic spines (Irwin et al, , 2000).

Currently available treatments for NDDs are symptomatic – focusing on the management of symptoms – and supportive, requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Educational and social skills training and therapies are implemented early to address core issues of learning delay and social impairments. Special academic, social, vocational, and support services are often required. Medication, psychotherapy or behavioral therapy may be used for management of co-occurring anxiety, ADHD, depression, maladaptive behaviors (such as aggression) and sleep issues, Antiepileptic drugs may be used to control seizures.

Patent

WO 2014085480,

https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2014085480

EP 0 366 638 discloses GPE (a tri-peptide consisting of the amino acids Gly-Pro-Glu) and its di-peptide derivatives Gly-Pro and Pro-Glu. EP 0 366 638 discloses that GPE is effective as a neuromodulator and is able to affect the electrical properties of neurons.

WO95/172904 discloses that GPE has neuroprotective properties and that administration of GPE can reduce damage to the central nervous system (CNS) by the prevention or inhibition of neuronal and glial cell death.

WO 98/14202 discloses that administration of GPE can increase the effective amount of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in the central nervous system (CNS).

WO99/65509 discloses that increasing the effective amount of GPE in the CNS, such as by administration of GPE, can increase the effective amount of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the CNS to increase TH-mediated dopamine production in the treatment of diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

WO02/16408 discloses certain GPE analogs having amino acid substitutions and certain other modification that are capable of inducing a physiological effect equivalent to GPE within a patient. The applications of the GPE analogs include the treatment of acute brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases, including injury or disease in the CNS.

EXAMPLES

The following examples are intended to illustrate embodiments of this invention, and are not intended to limit the scope to these specific examples. Persons of ordinary skill in the art can apply the disclosures and teachings presented herein to develop other embodiments without undue experimentation and with a likelihood of success. All such embodiments are considered part of this invention.

Example 1: Synthesis of N,N-Dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl)-L-glutamic acid

The following non-limiting example illustrates the synthesis of a compound of the invention, N,N-Dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

All starting materials and other reagents were purchased from Aldrich; BOC=tert-butoxycarbonyl; Bn=benzyl.

BOC-L-proline-(P-benzyl)-L-glutamic acid benzyl ester

To a solution of BOC-proline [Anderson GW and McGregor AC: J. Amer. Chem. Soc: 79, 6810, 1994] (10 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 mi), cooled to 0°C, was added triethylamine (1 .39 ml, 10 mmol) and ethyl chloroformate (0.96 ml, 10 mmol). The resultant mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 minutes. A solution of dibenzyl-L-glutamate (10 mmol) was then added and the mixture stirred at 0° C for 2 hours then warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was washed with aqueous sodium bicarbonate and citric acid (2 mol 1-1) then dried (MgSO4) and concentrated at reduced pressure to give BOC-L-proline-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (5.0 g, 95%).

L-proline-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester

A solution of BOC-L-glutamyl-L-proline dibenzyl ester (3.4 g, 10 mmol), cooled to 0 °C, was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (25 ml) for 2 h. at room temperature. After removal of the volatiles at reduced pressure the residue was triturated with ether to give L-proline-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester.

N,N-Dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

A solution of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 ml) was added to a stirred and cooled (0 °C) solution of L-proline-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (10 mmol), N,N-dimethylglycine (10 mmol) and triethylamine ( 10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (30 ml). The mixture was stirred at 0°C overnight and then at room temperature for 3 h. After filtration, the filtrate was evaporated at reduced pressure. The resulting crude dibenzyl ester was dissolved in a mixture of ethyl acetate (30 ml) and methanol (30 ml) containing 10% palladium on charcoal (0.5 g) then hydrogenated at room temperature and pressure until the uptake of hydrogen ceased. The filtered solution was evaporated and the residue recrystallised from ethyl acetate to yield the tripeptide derivative.

It can be appreciated that following the method of the Examples, and using alternative amino acids or their amides or esters, will yield other compounds of Formula 1.

Eample 2: Synthesis of Glycyl-L-2-Methyl-L-Prolyl-L-Glutamate

L-2-Methylproline and L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester p-toluenesulphonate were purchased from Bachem, N-benzyloxycarbonyl-glycine from Acros Organics and bis(2-oxo-3-oxazolidinyl)phosphinic chloride (BoPCl, 97%) from Aldrich Chem. Co.

Methyl L-2-methylprolinate hydrochloride 2

Thionyl chloride (5.84 cm3, 80.1 mmol) was cautiously added dropwise to a stirred solution of (L)-2-methylproline 1 (0.43 g, 3.33 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (30 cm3) at -5 °C under an atmosphere of nitrogen. The reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 24 h, and the resultant pale yellow-coloured solution was. concentrated to dryness in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in a 1 : 1 mixture of methanol and toluene (30 cm3) then concentrated to dryness to remove residual thionyl chloride. This procedure was repeated twice more, yielding hydrochloride 2 (0.62 g, 104%) as an hygroscopic, spectroscopically pure, off-white solid: mp 127- 131 °C; [α]D -59.8 (c 0.24 in CH2Cl2); vmax (film)/cm-1 3579, 3398 br, 2885, 2717, 2681 , 2623, 2507, 1743, 1584, 1447, 1432, 1374, 1317, 1294, 1237, 1212, 1172, 1123, 981 , 894, 861 and 764; δH (300 MHz; CDCl3; Me4Si) 1.88 (3H, s, Proα-CH3), 1 .70-2.30 (3H, br m, Proβ-HAΗΒ and Proγ-H2), 2.30-2.60 (1H, br m, Proβ-HAΗΒ), 3.40-3.84 (2H, br m, Proδ-H2), 3.87 (3H, s, CO2CH3), 9.43 (1H, br s, NH) and 10.49 ( 1H, br s, HCl); δC (75 MHz; CDCl3) 21.1 (CH3, Proα-CH3), 22.4 (CH2, Proγ-C), 35.6 (CH2, Proβ-C), 45.2 (CH2, Proδ-C), 53.7 (CH3, CO2CH3), 68.4 (quat., Proα-C) and 170.7 (quat, CO); m/z (FAB+) 323.1745 [M2.H35Cl.H+: (C7H13NO2)2. H35Cl.H requires 323.1738] and 325.1718 [M2.H37Cl.H+: (C7H13NOz)2. H37Cl.H requires 325.1708],

N-Benxyloxycarbonyl-glycyl-L-2-methylproline 5

Anhydrous triethylamine (0.45 cm3, 3.23 mmol) was added dropwise to a mixture of methyl L-2-methylprolinate hydrochloride 2 (0.42 g, 2.34 mmol) and N-benzyloxycarbonyl-glycine (98.5%) 3 (0.52 g, 2.45 mmol) in methylene chloride (16 cm3), at 0 °C, under an atmosphere of nitrogen. The resultant solution was stirred for 20 min and a solution of 1 ,3-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.56 g, 2.71 mmol) in methylene chloride (8 cm3) at 0 °C was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for a further 20 h. The resultant white mixture was filtered through a Celite pad to partially remove 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea, and the pad was washed with methylene chloride (50 cm3). The filtrate was washed successively with 10% aqueous hydrochloric acid (50 cm3) and saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate (50 cm3), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. Further purification of the residue by flash column chromatography (35 g SiO2; 30-70% ethyl acetate – hexane; gradient elution) afforded tentatively methyl N-benzyloxycarbonyl-glycyl-L-2-methylprolinate 4 (0.56 g), containing 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea, as a white semi-solid: Rf 0.65 (EtOAc); m/z (ΕI+) 334.1534 (M+. C17H22N2O5 requires 334.1529) and 224 ( 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea).

pad to partially remove 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea, and the pad was washed with methylene chloride (50 cm3). The filtrate was washed successively with 10% aqueous hydrochloric acid (50 cm3) and saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate (50 cm3), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. Further purification of the residue by flash column chromatography (35 g SiO2; 30-70% ethyl acetate – hexane; gradient elution) afforded tentatively methyl N-benzyloxycarbonyl-glycyl-L-2-methylprolinate 4 (0.56 g), containing 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea, as a white semi-solid: Rf 0.65 (EtOAc); m/z (ΕI+) 334.1534 (M+. C17H22N2O5 requires 334.1529) and 224 ( 1 ,3-dicyclohexylurea).

To a solution of impure prolinate 4 (0.56 g, ca. 1.67 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (33 cm3) was added dropwise 1 M aqueous sodium hydroxide (10 cm3, 10 mmol) and the mixture was stirred for 19 h at room temperature. Methylene chloride ( 100 cm3) was then added and the organic layer extracted with saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate (2 x 100 cm3). The combined aqueous layers were carefully acidified with hydrochloric acid (32%), extracted with methylene chloride (2 x 100 cm3), and the combined organic layers dried (MgSO4), filtered, and

concentrated to dryness in vacuo. Purification of the ensuing residue (0.47 g) by flash column chromatography ( 17 g SiO2; 50% ethyl acetate – hexane to 30% methanol – dichloromethane; gradient elution) gave N-protected dipeptide 5 (0.45 g, 60%) as a white foam in two steps from hydrochloride 2. Dipeptide 5 was shown to be exclusively the frafw-orientated conformer by NMR analysis: Rf 0.50 (20% MeOH – CH2Cl2); [α]D -62.3 (c 0.20 in CH2Cl2); vmax (film)/cm-1 3583, 3324 br, 2980, 2942, 1722, 1649, 1529, 1454, 1432, 1373, 1337, 1251 , 1219, 1179, 1053, 1027, 965, 912, 735 and 698; δH (300 MHz; CDCl3; Me4Si) 1.59 (3H, s, Proα-CH3), 1 .89 (1H, 6 lines, J 18.8, 6.2 and 6.2, Proβ-HAHB), 2.01 (2H, dtt, J 18.7, 6.2 and 6.2, Proγ-H2), 2.25-2.40 (1H, m, Proβ-HAΗΒ), 3.54 (2H, t, J 6.6, Proδ-H2), 3.89 (1H, dd, J 17.1 and 3.9, Glyα-HAHB), 4.04 (1H, dd, J 17.2 and 5.3, Glyα-HAΗΒ), 5.11 (2H, s, OCH2Ph), 5.84 (I H, br t, J 4.2, N-H), 7.22-7.43 (5H, m, Ph) and 7.89 (1 H, br s, -COOH); δC (75 MHz; CDCl3) 21.3 (CH3, Proα-CH3), 23.8 (CH2, Proγ-C), 38.2 (CH2, Proβ-C), 43.6 (CH2, Glyα-C), 47.2 (CH2, Proδ-C), 66.7 (quat, Proα-C), 66.8 (CH2, OCH2Ph), 127.9 (CH, Ph), 127.9 (CH, Ph), 128.4, (CH, Ph), 136.4 (quat., Ph), 156.4 (quat., NCO2), 167.5 (quat., Gly-CON) and 176.7 (quat., CO); m/z (EI+) 320.1368 (M+. C16Η20Ν2Ο5 requires 320.1372).

Dibenzyl N-benzyloxycarbonyl-glycyl-L-2-methylprolyl-L-glutamate 7

Triethylamine (0.50 cm3, 3.59 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of dipeptide 5 (0.36 g, 1.12 mmol) and L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester /Moluenesulphonate 6 (0.73 g, 1.46 mmol) in methylene chloride (60 cm3) under nitrogen at room temperature, and the reaction mixture stirred for 10 min. Bis(2-oxo-3-oxazoIidinyl)phosphinic chloride (BoPCl, 97%) (0.37 g, 1.41 mmol) was added and the colourless solution stirred for 17 h. The methylene chloride solution was washed successively with 10% aqueous hydrochloric acid (50 cm3) and saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate (50 cm3), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and evaporated to dryness in vacuo. Purification of the resultant residue by repeated (2x) flash column chromatography (24 g SiO2; 30-70% ethyl acetate – hexane; gradient elution) yielded ƒully protected tripeptide 7 (0.63 g, 89%) as a colourless oil. Tripeptide 7 was shown to be exclusively the trans-orientated conformer by NMR analysis: Rf 0.55 (EtOAc); [α]D -41.9 (c 0.29 in CH2Cl2); vmax (film)/cm-1 3583, 3353 br, 2950, 1734, 1660, 1521, 1499, 1454, 1429, 1257, 1214, 1188, 1166, 1051, 911, 737 and 697; δH (400 MHz; CDCl3; Me4Si) 1.64 (3H, s, Proot-CH3), 1.72 (1H, dt, J 12.8, 7.6 and 7.6, Proβ-HAHB), 1.92 (2H, 5 lines, J 6.7, Proγ-H2), 2.04 (1H, 6 lines, J 7.3 Gluβ-HAHB), 2.17-2.27 (1H, m, Gluβ-HAΗΒ), 2.35-2.51 (3H, m, Proβ-HAΗΒ and Gluγ-H2), 3.37-3.57 (2H, m, Proδ-H2), 3.90 (1 H, dd, J 17.0 and 3.6, Glyα-HAHB), 4.00 (1H, dd, J 17.1 and 5.1, Glyα-HAΗΒ), 4.56 (1H, td, J 7.7 and 4.9, Glyα-H), 5.05-5.20 (6H, m, 3 x OCH2Ph), 5.66-5.72 (1H, br m, Gly-NH), 7.26-7.37 (15H, m, 3 x Ph) and 7.44 (1H, d, J 7.2, Glu-NH); δC (100 MHz; CDCl3) 21.9 (CH3, Proα-CH3), 23.4 (CH2, Proγ-C), 26.6 (CH2, Gluβ-C), 30.1 (CH2, Gluγ-C), 38.3 (CH2, Proβ-C),

43.9 (CH2, Glyα-C), 47.6 (CH2, Proδ-C), 52.2 (CH, Glua-C), 66.4 (CH2, OCH2Ph), 66.8 (CH2, OCH2Ph), 67.1 (CH2, OCH2Ph), 68.2 (quat, Proα-C), 127.9 (CH, Ph), 128.0 (CH, Ph), 128.1, (CH, Ph), 128.2, (CH, Ph), 128.2, (CH, Ph), 128.3, (CH, Ph), 128.4, (CH, Ph), 128.5, (CH, Ph), 128.5, (CH, Ph), 135.2 (quat., Ph), 135.7 (quat., Ph), 136.4 (quat, Ph), 156.1 (quat, NCO2), 167.3 (quat., Gly-CO), 171.4 (quat., CO), 172.9 (quat., CO) and 173.4 (quat., CO); m/z (FAB+) 630.2809 (MH+. C35H40N3O8 requires 630.2815).

Glycyl-L-2-methylprolyl-L-glutamic acid (G-2-MePE)

A mixture of the protected tripeptide 7 (0.63 g, 1.00 mmol) and 10 wt % palladium on activated carbon (0.32 g, 0.30 mmol) in 91 :9 methanol – water (22 cm3) was stirred under an atmosphere of hydrogen at room temperature, protected from light, for 23 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite pad and the pad washed with 75 :25 methanol – water (200 cm3). The filtrate was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure and the residue triturated with anhydrous diethyl ether to afford a 38: 1 mixture of G-2-MePE and tentatively methylamine 8 (0.27 g, 86%) as an extremely hygroscopic white solid. Analytical reverse-phase HPLC studies on the mixture [Altech Econosphere C 18 Si column, 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 ☐m; 5 min flush with H2O (0.05% TFA) then steady gradient over 25 min to MeCN as eluent at flow rate of 1 ml/min; detection using diode array] indicated it was a 38: 1 mixture of two eluting peaks with retention times of 13.64 and 14.44 min at 207 and 197 nm, respectively. G-2-MePE was shown to be a 73 :27 trans:cis mixture of conformers by 1H NMR analysis (the ratio was estimated from the relative intensities of the double doublet and triplet at δ 4.18 and 3.71 , assigned to the Gluα-H protons of the major and minor conformers, respectively):

pad and the pad washed with 75 :25 methanol – water (200 cm3). The filtrate was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure and the residue triturated with anhydrous diethyl ether to afford a 38: 1 mixture of G-2-MePE and tentatively methylamine 8 (0.27 g, 86%) as an extremely hygroscopic white solid. Analytical reverse-phase HPLC studies on the mixture [Altech Econosphere C 18 Si column, 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 ☐m; 5 min flush with H2O (0.05% TFA) then steady gradient over 25 min to MeCN as eluent at flow rate of 1 ml/min; detection using diode array] indicated it was a 38: 1 mixture of two eluting peaks with retention times of 13.64 and 14.44 min at 207 and 197 nm, respectively. G-2-MePE was shown to be a 73 :27 trans:cis mixture of conformers by 1H NMR analysis (the ratio was estimated from the relative intensities of the double doublet and triplet at δ 4.18 and 3.71 , assigned to the Gluα-H protons of the major and minor conformers, respectively):

mp 144 °Cɸ;

[ α]D -52.4 (c 0.19 in H2O);

δα (300 MHz; D2O; internal MeOH) 1.52 (3H, s, Proα-CH3), 1.81-2.21 (6H, m, Proβ-H2, Proγ-H, and Gluβ-H2), 2.34 (1.46H, t, J 7.2, Gluy-H2), 2.42* (0.54H, t, 77.3, Gluγ-H2), 3.50-3.66 (2H, m, Pro6-H2), 3.71 * (0.27H, t, J 6.2, Gluoc-H), 3.85 (1H, d, J 16.6, Glyα-HAHB), 3.92 (1H, d, J 16.6, Glyα-HAΗΒ) and 4.18 (0.73H, dd, J 8.4 and 4.7, Glua-H);

δC (75 MHz; D2O; internal MeOH) 21.8 (CH3, Proα-CH3), 25.0 (CH2, Proγ-C), 27.8* (CH2: Gluβ-C), 28.8 (CH2, Gluβ-C), 32.9 (CH2, Gluγ-C), 40.8 (CH2, Proβ-C), 42.7 (CH2, Glyα-C), 49.5 (CH2, Proδ-C), 56.0* (CH, Gluα-C), 56.4 (CH, Gluα-C), 69.8 (quat, Proα-C), 166.5 (quat., Gly-CO), 177.3 (quat., Pro-CON), 179.2 (quat., Gluα-CO), 180.2* (quat., Gluγ-CO) and 180.6 (quat., Gluγ-CO);

m/z (FAB+) 3 16.1508 (MH+. C13H22N3O6 requires 316.1509).

PATENT

WO02094856

Example

The following non-limiting example illustrates the synthesis of a compound of the invention, NN-dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid.

All starting materials and other reagents were purchased from Aldrich;

BOC = tert-butoxycarbonyl; Bn = benzyl.

BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid benzyl ester

To a solution of BOC-proline [Anderson GW and McGregor AC: J. Amer. Chem.

Soc: 79, 6180, 1957] (10 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 ml), cooled to 0 °C, was added triethylamine (1.39 ml, 10 mmol) and ethyl chloroformate (0.96 ml, 10 mmol). The resultant mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 minutes. A solution of dibenzyl L-glutamate (10 mmol) was then added and the mixture stirred at 0 °C for 2 hours then warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was washed with aqueous sodium bicarbonate and citric acid (2 mol l“1) then dried (MgS04) and concentrated at reduced pressure to give BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (5.0 g, 95%).

(7-Benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester

A solution of BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (3.4 g, 10 mmol), cooled to 0 °C, was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (25 ml) for 2 hr at room temperature. After removal of the volatiles at reduced pressure the residue was triturated with ether to give (γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (I).

N,N-Dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

A solution of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 ml) was added to a stirred and cooled (0 °C) solution of (7-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (10 mmol), TVN-dimethylglycine (10 mmol) and triethylamine

(10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (30 ml). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C overnight and then at room temperature for 3 h. After filtration, the filtrate was evaporated at reduced pressure. The resulting crude dibenzyl ester was dissolved in a mixture of ethyl acetate (30 ml) and methanol (30 ml) containing 10% palladium on charcoal (0.5 g) then hydrogenated at room temperature and pressure until the uptake of hydrogen ceased. The filtered solution was evaporated and the residue recrystallized from ethyl acetate to yield the tri-peptide derivative.

It will be evident that following the method of the Example, and using alternative amino acids or their amides or esters, will yield other compounds of Formula 1.

Testing; Material and Methods

The following experimental protocol followed guidelines approved by the

University of Auckland animal ethics committee.

Preparation of cortical astrocyte cultures for harvest of metabolised cell culture supernatant

One cortical hemisphere from a postnatal day 1 rat was used and collected into

4ml of DMEM. Trituration was done with a 5ml glass pipette and subsequently through an 18 gauge needle. Afterwards, the cell suspension was sieved through a lOOμm cell strainer and washed in 50ml DMEM (centrifugation for 5min at 250g). The sediment was resuspended into 20ml DMEM+10% fetal calf serum. 10 Milliliters of suspension was added into each of two 25cm3 flasks and cultivated at 37°C in the presence of 10% C02, with a medium change twice weekly. After cells reached confluence, they were washed three times with PBS and adjusted to Neurobasal/B27 and incubated for another 3 days. This supernatant was frozen for transient storage until usage at -80°C.

Preparation of striatal and cortical tissue from rat E18/E19 embryos

A dam was sacrificed by C02-treatment in a chamber for up to 4 minutes and was prepared then for cesarean section. After surgery, the embryos were removed from their amniotic sacs, decapitated and the heads put on ice in DMEM/F12 medium for striatum and PBS + 0.65% D(+)-glucose for cortex.

Striatal tissue extraction procedure and preparation of cells

Whole brain was removed from the skull with the ventral side facing upside in DMEM/F12 medium. The striatum was dissected out from both hemispheres under a stereomicroscope and the striatal tissue was placed into the Falcon tube on ice.

The collected striatal tissue was triturated by using a PI 000 pipettor in 1ml of volume. The tissue was triturated by gently pipetting the solution up and down into the pipette tip about 15 times, using shearing force on alternate outflows. The tissue pieces settled to the bottom of the Falcon tube within 30 seconds, subsequently the supernatant was transferred to a new sterile Falcon tube on ice. The supernatant contained a suspension of dissociated single cells. The tissue pieces underwent a second trituration to avoid excessively damaging cells already dissociated by over triturating them. 1 Milliliter of ice-cold DMEM/F12 medium was added to the tissue pieces in the first tube and triturated as before. The tissue pieces were allowed to settle and the supernatant was removed to a new sterile Falcon tube on ice. The cells were centrifuged at 250g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The resuspended cell pellet was ready for cell counting.

Plating and cultivation of striatal cells

Striatal cells were plated into Poly-L-Lysine (O.lmg/ml) coated 96-well plates (the inner 60 wells only) at a density of 200,000 cells /cm2 in Neurobasal/B27 medium (Invitrogen). The cells were cultivated in the presence of 5% C02 at 37°C under 100% humidity. Complete medium was changed on days 1, 3 and 6.

Cortical tissue extraction procedure and preparation of cells

The two cortical hemispheres were carefully removed by a spatula from the whole brain with the ventral side facing upside into a PBS +0.65% D(+)-glucose containing petri dish. Forcips were put into the rostral part (near B. olfactorius) of the cortex for fixing the tissue and two lateral – sagittal oriented cuttings were done to remove the paraform and entorhinal cortices. The next cut involved a frontal oriented cut at the posterior end to remove the hippocampal formation. A final frontal cut was done a few millimeters away from the last cut in order to get hold of area 17/18 of the visual cortex.

The collected cortices on ice in PBS+0.65% D(+)-glucose were centrifuged at 350g for 5min. The supernatant was removed and trypsin/EDTA (0.05%/0.53mM) was added for 8min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal amount of DMEM+10%) fetal calf serum. The supernatant was removed by centrifugation followed by two subsequent washes in Neurobasal/B27 medium.

The cells were triturated once with a glass Pasteur pipette in 1 ml of

Neurobasal/B27 medium and subsequently twice by using a 1ml insulin syringe with a 22 gauge needle. The cell suspension was passed through a lOOμm cell strainer and subsequently rinsed by 1ml of Neurobasal B27 medium. Cells were counted and adjusted to 50,000 cells per 60μl.

Plating and cultivation of cortical cells

96-well plates were coated with 0.2mg/ml Poly-L-Lysine and subsequently coated with 2μg/ml laminin in PBS, after which 60μl of cortical astrocyte-conditioned medium was added to each well. Subsequently, 60μl of cortical cell suspension was added. The cells were cultivated in the presence of 10% C02 at 37°C under 100%) humidity. At day 1, there was a complete medium change (1:1- Neurobasal/B27 and astrocyte-conditioned medium) with addition of lμM cytosine-β-D-arabino-furanoside (mitosis inhibitor). On the second day, 2/3 of medium was changed. On day 5, 2/3 of the medium was changed again.

Cerebellar microexplants from P8 animals: preparation, cultivation and fixation

The laminated cerebellar cortices of the two hemispheres were explanted from a P8 rat, cut into small pieces in PBS + 0.65% D(+)glucose solution and triturated by a 23gauge needle and subsequently pressed through a 125 μm pore size sieve. The microexplants that were obtained were centrifuged (60 g) twice (media exchange) into serum-free BSA-supplemented START V-medium (Biochrom). Finally, the

microexplants were reconstituted in 1500 μl STARTV-medium (Biochrom). For cultivation, 40μl of cell suspension was adhered for 3 hours on a Poly-D-Lysine

(O.lmg/ml) coated cover slip placed in 35mm sized 6-well plates in the presence of 5% C02 under 100% humidity at 34°C. Subsequently, 1ml of STARTV-medium was added together with the toxins and drugs. The cultures were monitored (evaluated) after 2-3 days of cultivation in the presence of 5% C02 under 100% humidity. For cell counting analysis, the cultures were fixed in rising concentrations of paraformaldehyde (0.4%, 1.2%, 3% and 4% for 3min each) followed by a wash in PBS.

Toxin and drug administration for cerebellar, cortical and striatal cells: analysis

All toxin and drug administration experiments were designed that 1/100 parts of okadaic acid (30nM and lOOnM concentration and 0.5mM 3-nitropropionic acid for cerebellar microexplants only), GPE (InM -ImM) and G-2Methyl-PE (InM-lmM) were used respectively at 8DIV for cortical cultures and 9DIV for striatal cultures. The incubation time was 24hrs. The survival rate was determined by a colorimetric end-point MTT-assay at 595nm in a multi-well plate reader. For the cerebellar microexplants four windows (field of 0.65 mm2) with highest cell density were chosen and cells displaying neurite outgrowth were counted.

Results

The GPE analogue G-2Methyl-PE exhibited comparable neuroprotective capabilities within all three tested in vitro systems (Figures 12-15).

The cortical cultures responded to higher concentrations of GPE (Figure 12) /or

G-2Methyl-PE (lOμM, Figure 13) with 64% and 59% neuroprotection, respectively.

Whereas the other 2 types of cultures demonstrated neuroprotection at lower doses of G-2Methyl-PE (Figures 14 and 15). The striatal cells demonstrated

neuroprotection within the range of InM to ImM of G-2Methyl-PE (Figure 15) while the postnatal cerebellar microexplants demonstrated neuroprotection with G-2Methyl-PE in the dose range between InM and lOOnM (Figure 14).

While this invention has been described in terms of certain preferred embodiments, it will be apparent to a person of ordinary skill in the art having regard to that knowledge and this disclosure that equivalents of the compounds of this invention may be prepared and administered for the conditions described in this application, and all such equivalents are intended to be included within the claims of this application.

PATENT

WO-2021026066

Composition and kits comprising trofinetide and other related substances. Also claims a process for preparing trofinetide and the dosage form comprising the same. Disclosed to be useful in treating neurodegenerative conditions, autism spectrum disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Trofinetide is a synthetic compound, having a similar core structure to Glycyl-Prolyl-Glutamic acid (or “GPE”). Trofinetide has been found to be useful in treating neurodegenerative conditions and recently has been found to be effective in treating Autism Spectrum disorders and Neurodevelopmental disorders.

Formula (Ila),

Example 1: Trofinetide Manufacturing Process

In general, trofinetide and related compounds can be manufactured from a precursor peptide or amino acid reacted with a silylating or persilylating agent at one or more steps. In the present invention, one can use silylating agents, such as N-trialkylsilyl amines or N-trialkylsilyl amides, not containing a cyano group.

Examples of such silylating reagents include N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA), N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide, hexamethyldisilazane, N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (TMA), N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)acetamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)diethylamine, N-(trimethylsilyl)dimethylamine, 1-(trimethylsilyl)imidazole, 3-(trimethylsilyl)-2-oxazolidone.

Step 1: Preparation of Z-Gly-OSu

Several alternative procedures can be used for this step.

Procedure 1A

One (1) eq of Z-Gly-OH and 1.1 eq of Suc-OH were solubilized in 27 eq of iPrOH and 4 eq of CH2Cl2 at 21 °C. The mixture was cooled and when the temperature reached -4 °C, 1.1 eq of EDC.HCl was added gradually, keeping the temperature below 10 °C. During the reaction a dense solid appeared. After addition of EDC.HCl, the mixture was allowed to warm to 20 °C. The suspension was cooled to 11 °C and filtered. The cake was washed with 4.9 eq of cold iPrOH and 11 eq of IPE before drying at 34 °C (Z-Gly-OSu dried product -Purity: 99.5%; NMR assay: 96%; Yield: 84%).

Procedure 1B

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 1A, and differs by replacing iPrOH with ACN. One (1) eq of Z-Gly-OH and 1.1 eq of Suc-OH were solubilized in 22 eq of ACN at 35 °C. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath. When the temperature reached 1 °C, 0.9 eq of DCC in 5.5 eq of ACN was added gradually to keep the temperature below 5 °C. The coupling reaction took about 20 hrs. During the reaction, DCU precipitated and was removed by filtration at the end of the coupling. After filtration, DCU was washed with ACN to recover the product. The mixture of Z-Gly-OSu was then concentrated to reach 60% by weight. iPrOH (17 eq) was added to initiate the crystallization. Quickly after iPrOH addition a dense solid appeared. An additional 17 eq of iPrOH was needed to liquify the suspension. The suspension was cooled in an ice bath and filtered. The solid was washed with 9 eq of iPrOH before drying at 45 °C (Z-Gly-OSu dried product – Purity: 99.2%; HPLC assay: 99.6%; Yield: 71%).

Step 2: Preparation of Z-Gly-MePro-OH

Several alternative procedures can be used for this step.

Procedure 2A

One (1) eq of MePro.HCl was partially solubilized in 29 eq of CH2Cl2 at 35 °C with 1.04 eq of TEA and 1.6 eq of TMA. The mixture was heated at 35 °C for 2 hrs to perform the silylation. Then 1.02 eq of Z-Gly-OSu was added to the mixture. The mixture was kept at 35 °C for 3 hrs and then 0.075 eq of butylamine was added to quench the reaction. The mixture was allowed to return to room temperature and mixed for at least 15 min. The Z-Gly-MePro-OH was extracted once with 5% w/w NaHCO3 in 186 eq of water, then three times successively with 5% w/w NaHCO3 in 62 eq of water. The aqueous layers were pooled and the pH was brought to 2.2 by addition of 34 eq of HCl as 12N HCl at room temperature. At this pH, Z-Gly-MePro-OH formed a sticky solid that was solubilized at 45 °C with approximately 33 eq of EtOAc and 2.3 eq of iButOH. Z-Gly-MePro-OH was extracted into the organic layer and washed with 62 eq of demineralized water. The organic layer was then dried by azeotropic distillation with 11.5 eq of EtOAc until the peptide began to precipitate. Cyclohexane (12 eq) was added to the mixture to complete the precipitation. The suspension was cooled at 5 °C for 2 hrs and filtered. The solid was washed with 10 eq of cyclohexane before drying at 45 °C (Z-Gly-MePro-OH dried product – Purity: 100%; HPLC assay: 100%; Yield 79%).

Procedure 2B

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 2A. One (1) eq of MePro.HCl was partially solubilized in 36.6 eq of CH2Cl2 at 34 °C with 1.01 eq of TEA and 0.1 eq of TMA. Then 1.05 eq of Z-Gly-OSu was added to the mixture, followed by 1.0 eq of TEA. The mixture was maintained at 35 °C for approximately 1 hr, cooled to 25 to 30 °C and 0.075 eq of DMAPA was added to stop the reaction. One hundred (100) eq of water, 8.6 eq of HCl as 12N HCl and 0.3 eq of KHSO4 were added to the mixture (no precipitation was observed, pH=1.7). Z-Gly-MePro-OH was extracted into the organic layer and washed twice with 97 eq of demineralized water with 0.3 eq of KHSO4, then 100 eq of demineralized water, respectively. EtOAc (23 eq) was added to the mixture and CH2Cl2 was removed by distillation until the peptide began to precipitate. Cyclohexane (25 eq) was added to the mixture to complete the precipitation. The suspension was cooled at -2 °C overnight and filtered. The solid was washed with 21 eq of cyclohexane before drying at 39 °C (Z-Gly-MePro-OH dried product – Purity: 98.7%; NMR assay: 98%; Yield 86%).

Procedure 2C

In reactor 1, MePro.HCl (1 eq) was suspended in EtOAc (about 7 eq). DIPEA (1 eq) and TMA (2 eq) were added, and the mixture heated to dissolve solids. After dissolution, the solution was cooled to 0 °C. In reactor 2, Z-Gly-OH (1 eq) was suspended in EtOAc (about 15 eq). DIPEA (1 eq), and pyridine (1 eq) were added. After mixing, a solution was obtained, and cooled to -5 °C. Piv-Cl (1 eq) was added to reactor 2, and the contents of reactor 1 added to reactor 2. Upon completed addition, the contents of reactor 2 were taken to room temperature. The conversion from Z-Gly-OH to Z-Gly-MePro-OH was monitored by HPLC. When the reaction was complete, the reaction mixture was quenched with DMAPA (0.1 eq), and washed with an aqueous solution comprised of KHSO4, (about 2.5 wt%), NaCl (about 4 wt%), and conc. HCl (about 6 wt%) in 100 eq H2O. The aqueous layer was re-extracted with EtOAc, and the combined organic layers washed with an aqueous solution comprised of KHSO4 (about 2.5 wt%) and NaCl (about 2.5 wt%) in 100 eq H2O, and then with water (100 eq). Residual water was removed from the organic solution of Z-Gly-MePro-OH by vacuum distillation with EtOAc. The resulting suspension was diluted with heptane (about 15 eq) and cooled to 0 °C. The product was isolated by filtration, washed with cold heptane (about 7 eq), and dried under vacuum at 45 °C. Z-Gly-MePro-OH (85% yield) was obtained.

Step 3: Preparation of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH

Several alternative procedures can be used in this step.

Procedure 3A

H-Glu-OH (1.05 eq) was silylated in 2 eq of CH2Cl2 with 3.5 eq of TMA at 65 °C. Silylation was completed after 2 hrs. While the silylation was ongoing, 1.0 eq of Z-Gly-MePro-OH and 1.0 eq of Oxyma Pure were solubilized in 24 eq of CH2Cl2 and 1.0 eq of DMA at room temperature in another reactor. EDC.HCl (1.0 eq.) was added. The activation rate reached 97% after 15 min. The activated Oxyma Pure solution, was then added to silylated H-Glu-OH at 40 °C and cooled at room temperature. Coupling duration was approximately 15 min, with a coupling rate of 97%. Addition of 8.2% w/w NaHCO3 in 156 eq of water to the mixture at room temperature (with the emission of CO2) was performed to reach pH 8. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was extracted in water. The aqueous layer was washed twice with 29 eq of CH2Cl2. Residual CH2Cl2 was removed by concentration. The pH was brought to 2.5 with 2.5N HCl, followed by 1.4 eq of solid KHSO4 to precipitate Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH. The mixture was filtered and the solid was washed with 3 x 52 eq of water. The filtered solid was added to 311 eq of demineralized water and heated to 55-60 °C. iPrOH (29 eq) was added gradually until total solubilization of the product. The mixture was slowly cooled to 10 °C under moderate mixing during 40 min to initiate the crystallization. The peptide was filtered and washed with 2 x 52 eq of water before drying at 45 °C (Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH dried product – Purity: 99.5%; NMR assay: 96%; Yield 74%).

Procedure 3B

One (1) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-OH and 1.05 eq of Suc-OH were solubilized in 40 eq of ACN and 30 eq of CH2Cl2 at room temperature. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath, and when the temperature was near 0 °C, 1.05 eq of DCC dissolved in 8 eq of ACN was added gradually, keeping the temperature below 5 °C. After addition of DCC, the mixture was progressively heated from 0 °C to 5 °C over 1 hr, then to 20 °C between 1 to 2 hrs and then to 45 °C between 2 to 5 hrs. After 5 hrs, the mixture was cooled to 5 °C and maintained overnight. The activation rate reached 98% after approximately 24 hrs. DCU was removed by filtration and washed with 13.5 eq of ACN. During the activation step, 1.1 eq of H-Glu-OH was silylated in 30 eq of ACN with 2.64 eq of TMA at 65 °C. Silylation was completed after 2 hrs. Z-Gly-MePro-OSu was then added gradually to the silylated H-Glu-OH at room temperature, with 0.4 eq of TMA added to maintain the solubility of the H-Glu-OH. The mixture was heated to 45 °C and 0.7 eq of TMA was added if precipitation occurred. The coupling duration was about 24 hrs to achieve a coupling rate of approximately 91%. The reaction was quenched by addition of 0.15 eq of butylamine and 2.0 eq of TEA. Water (233 eq) was added and the mixture concentrated until gelation occurred. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was extracted in water by addition of 5% w/w NaHCO3 in 233 eq of water and 132 eq of CH2Cl2. The aqueous layer was washed twice with 44 eq of CH2Cl2. Residual CH2Cl2 was removed by distillation. The pH was brought to 2.0 with 24 eq of HCl as 12N HCl followed by 75 eq of HCl as 4N HCl. At this pH, Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH precipitated. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath over 1 hr and filtered. The solid was washed with 186 eq of cold water before drying at 45 °C (Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH dried product – HPLC Purity: 98.4%; NMR assay: 100%; Yield 55%).

Procedure 3C

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 3A. H-Glu-OH (1.05 eq) was silylated in 3.7 eq of CH2Cl2 with 3.5 eq of TMA at 62 °C. Silylation was completed after approximately 1.5 to 2 hrs, as evidenced by solubilization. During the silylation step, 1.0 eq of Z-Gly-MePro-OH and 1.0 eq of Oxyma Pure were solubilized in 31.5 eq of CH2Cl2 at 22 °C. One (1.06) eq of EDC.HCl was added to complete the activation. The silylated H-Glu-OH was then added to the activated Oxyma Pure solution. The temperature was controlled during the addition to stay below 45 °C. Desilylation was performed by addition of a mixture of 2.5% w/w KHSO4 in 153 eq of water and 9 eq of iPrOH to reach a pH of 1.65. Residual CH2Cl2 was removed by concentration. The mixture was cooled to 12 °C to precipitate the Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH. The mixture was filtered and the solid was washed with 90 eq of water before drying at 36 °C.

Procedure 3D

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 3A. H-Glu-OH (1.05 eq.) was silylated in 3.9 eq of CH2Cl2 with 3.5 eq of TMA at 62 °C. Silylation was completed after 2 hrs, as evidenced by Solubilization. During the silylation step, 1 eq of Z-Gly-MePro-OH and 1 eq of Oxyma Pure were solubilized in 25 eq of CH2Cl2 at 23 °C. One (1) eq of EDC.HCl was added. To complete the activation, an additional 0.07 eq of EDC. HCl was added. Silylated H-Glu-OH was then added to the activated Oxyma Pure solution. Temperature was controlled during the addition to stay below 45 °C. Desilylation was performed by addition of a mixture of 2.5% w/w KHSO4 in 160 eq of water and 9.6 eq of iPrOH to reach pH 1.63.

Residual CH2Cl2 was removed by concentration. The mixture was cooled to 20 °C to precipitate the Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH. The mixture was filtered and the solid was washed with 192 eq of water before drying at about 25 °C for 2.5 days. The solid was then solubilized at 64 °C by addition of 55 eq of water and 31 eq of iPrOH. After solubilization, the mixture was diluted with 275 eq of water and cooled to 10 °C for crystallization. The mixture was filtered and the solid was washed with 60 eq of water before drying at 27 °C (Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH dried product – Purity: 99.6%; NMR assay: 98%; Yield 74%).

Procedure 3E

In reactor 1, H-Glu-OH (1.05 eq) was suspended in ACN (about 2.2 eq). TMA (about 3.5 eq) added, and the mixture was heated to dissolve solids. After dissolution, the solution was cooled to room temperature. In reactor 2, Z-Gly-MePro-OH (1 eq) was suspended in ACN (14 eq). Oxyma Pure (1 eq) and EDC.HCl (1 eq) were added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature until the solids dissolved. The contents of reactor 2 were added to reactor 1. The conversion from Z-Gly-MePro-OH to Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was monitored by HPLC. Upon completion the reaction mixture was added to an aqueous solution comprised of KHSO4 (about 2.5 wt%) dissolved in about 100 eq H2O. ACN was removed from the aqueous suspension of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH by vacuum distillation with H2O. After stirring at room temperature, the product in the resulting suspension was isolated by filtration and washed with water. The solid obtained was dissolved in an aqueous solution comprised of NaHCO3 (about 5 wt%) in 110 eq H2O, and recrystallized by addition of an aqueous solution comprised of KHSO4 (about 10 wt%) in 90 eq H2O. The product was isolated by filtration, washed with water, and dried under vacuum at 45 °C. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH (75% yield) was obtained.

Step 4: Deprotection and Isolation of Trofinetide

Several alternative procedures can be used in this step.

Procedure 4A

Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH (1 eq) was suspended in water (about 25 eq) and EtOAc (about 15 eq). Pd/C (0.025 eq by weight and containing 10% Pd by weight) was added, and the reaction mixture hydrogenated by bubbling hydrogen through the reaction mixture at room temperature. The conversion from Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH to trofinetide was monitored by HPLC, and upon reaction completion the catalyst was removed by filtration, and the layers separated. Residual EtOAc was removed from the aqueous solution containing trofinetide by sparging with nitrogen or washing with heptane. The aqueous solution was spray-dried to isolate the product. Trofinetide (90% yield) was obtained. Alternatively, deprotection can be accomplished using MeOH only, or a combination of iPrOH and MeOH, or by use of ethyl acetate in water.

Procedure 4B

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A, excluding EtOAc. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH (1 eq) was suspended in water (about 50 eq). Pd/C (0.05 eq, 5% Pd by weight) was added, and the reaction mixture hydrogenated at room temperature with a pressure of 5 bar. The conversion from Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH to trofinetide was monitored by HPLC. Upon

reaction completion the catalyst was removed by filtration, and the aqueous layer washed with EtOAc (about 5 eq). Residual EtOAc was removed from the aqueous solution containing trofinetide by sparging with nitrogen or washing with heptane. The aqueous solution was spray-dried to isolate the product. Trofinetide (90% yield) was obtained.

Procedure 4C

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A, replacing EtOAc with MeOH. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH (1 eq) was suspended in MeOH (100 eq) and water (12 eq). Pd/Si (0.02 eq by weight) was added and the mixture was heated at 23 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. The conversion from Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH to trofinetide was monitored by HPLC, and upon reaction completion the catalyst was removed by filtration and the layers were washed with MeOH and iPrOH. The solvents were concentrated under vacuum at 45 °C, and trofinetide precipitated. The precipitate was filtered and dried at 45 °C to provide trofinetide.

Procedure 4D

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A, replacing Pd/C with Pd/Si. One (1.0) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was partially solubilized in 105 eq of MeOH and 12 eq of water. Pd/Si (0.02 eq by weight) was added and the mixture was heated at 23 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. At the end of the deprotection (conversion rate approximately 99% after 1 hr), the catalyst was filtered off and washed with 20-30 eq of MeOH. iPrOH (93 eq) was added and MeOH was replaced by iPrOH by concentration at 45 °C under vacuum. The peptide was concentrated until it began to precipitate. The peptide was filtered and dried at 45 °C (H-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH dried product: Purity: 98.1%; NMR assay: 90%; Yield 81%).

Procedure 4E

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A, removing H2O and replacing Pd/C with Pd/Si. One (1.0) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was partially solubilized in 44 eq of MeOH. Pd/Si type 340 (0.02 eq by weight) was added and the mixture was kept at 20 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. At the end of the deprotection (conversion rate about 99.9%, after 3-3.5 hrs), the catalyst was filtered off and washed with 8 eq of MeOH. Deprotected peptide was then precipitated in 56 eq of iPrOH. After 30 min at 5 °C, the peptide was filtered and washed with three times with 11 eq of iPrOH before drying at 25 °C (H-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH dried product: Purity: 99.4%; HPLC assay: ~98%; Yield: 81%).

Procedure 4F

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A. One (1) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was partially solubilized in 14 eq of EtOAc and 25 eq of water. Pd/C (0.01 eq by weight) was added and the mixture was kept at 20 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. At the end of the deprotection (conversion rate about 100%, after about 3.5 hrs), the catalyst was filtered off and washed with a mixture of 3.5 eq of EtOAc and 6 eq of water. The aqueous layer was then ready for spray-drying (Aqueous H-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH peptide solution: Purity: 98.6%; Yield: ~95%).

Procedure 4G

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A, replacing Pd/C with Pd/Si, EtOAc with MeOH, and removing H2O. Pd/Si type 340 (0.02 eq by weight) was added to 2.9 vols of MeOH for pre-reduction during 30 min. One (1.0) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was partially solubilized in 34 eq of MeOH. The reduced palladium was then transferred to the peptide mixture. The mixture was kept at 20 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. Pd/C type 39 (0.007 eq by weight) was added to the mixture to increase reaction kinetics. At the end of the deprotection, the catalyst was filtered off and washed with 13.6 eq of MeOH. The deprotected peptide was then precipitated in 71 eq of iPrOH. After about 40 min, the peptide was filtered and washed with 35 eq of iPrOH. The peptide was dried below 20 °C and was then ready for solubilization in water and spray-drying.

Procedure 4H

This Procedure is for a variant of Procedure 4A. One (1.0) eq of Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH was partially solubilized in 24.8 eq of water and 13.6 eq of EtOAc. Pd/C type 39 (0.025 eq by weight) was added to the peptide mixture. The mixture was kept at 20 °C for the hydrogenolysis. Solubilization of the peptide occurred during the deprotection. At the end of the deprotection (19 hrs), the catalyst was removed by filtration and washed with 5.3 eq of water and 2.9 eq of EtOAc. The biphasic mixture was then decanted to remove the upper organic layer. The aqueous layer was diluted with water to reach an H-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH concentration suitable for spray-drying the solution.

Example 2: Alternative Trofinetide Manufacturing Process

An alternative method for synthesis of Trofinetide is based on U.S. Patent No.

8,546,530 adapted for a tripeptide as follows.

The persilylated compounds used to synthesis Formula (Ia) (trofinetide) are obtained by silylating a corresponding peptide or amino acid by reaction with a silylating agent, optionally in an organic solvent. The persilylated peptide or amino acid can be isolated and purified if desired. One can use the persilylated peptide or amino acid in situ, e.g. by combining a solution containing persilylated peptide or amino acid with a solution containing, optionally activated, peptide or amino acid.

In step 2, the persilylated compound of an amino acid is obtained by silylating a corresponding amino acid (for example, H-MePro-OH) by reaction with a silylating agent, optionally in an organic solvent. The persilylated amino acid can be isolated and purified if desired. One can use the persilylated amino acid in situ, e.g. by combining a solution containing the persilylated amino acid with a solution containing, optionally activated, amino acid (for example, Z-Gly-OH).

In step 3, the persilylated compound of an amino acid is obtained by silylating a corresponding amino acid (for example, H-Glu-OH) by reaction with a silylating agent, optionally in an organic solvent. The persilylated amino acid or peptide can be isolated and purified if desired. It is however useful to use the persilylated amino acid or peptide in situ, e.g. by combining a solution containing the persilylated amino acid with a solution containing, optionally activated (for example, by using EDC.HCl and Oxyma Pure), peptide (for example, Z-Gly-MePro-OH).

In the present invention, it is useful to use silylating agents, such as N-trialkylsilyl amines or N-trialkylsilyl amides, not containing a cyano group. Examples of such silylating reagents include N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA), N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide, hexamethyldisilazane, N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (TMA), N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)acetamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)diethylamine, N-(trimethylsilyl)dimethylamine, 1-(trimethylsilyl)imidazole, 3-(trimethylsilyl)-2-oxazolidone.

The reaction of step 2 is generally carried out at a temperature from 0 °C to 100 °C, optionally from 10 °C to 40 °C, and optionally from 15 °C to 30 °C.

The reaction of step 3 is generally carried out at a temperature from 0 °C to 100 °C, optionally from 10 °C to 60 °C, optionally from 15 °C to 50 °C.

In the reaction of step 2, generally 0.5 to 5 equivalents, optionally 1 to 3 equivalents, optionally about 1.5 to 2.5 equivalents of silylating agent are used relative to the molar amount of functional groups to be silylated. Use of 2 to 4 equivalents of silylating agent relative to the molar amount of functional groups to be silylated is also possible. “Functional groups to be silylated” means particular groups having an active hydrogen atom that can react with the silylating agent such as amino, hydroxyl, mercapto or carboxyl groups.

In the reaction of step 3, generally 0.5 to 5 equivalents, optionally 2 to 4.5 equivalents, optionally about 3 to 4 equivalents of silylating agent are used relative to the molar amount of functional groups to be silylated. Use of 2.5 to 4.5 equivalents of silylating agent relative to the molar amount of functional groups to be silylated is also possible.

It is understood that “persilylated” means an amino acid or peptide or amino acid analogue or peptide analogue in which the groups having an active hydrogen atom that can react with the silylating agent are sufficiently silylated to ensure that a homogeneous reaction medium for a coupling step is obtained.

In the process according to the invention, the reaction between the amino acid or peptide and the persilylated amino acid or peptide is often carried out in the presence of a carboxyl group activating agent. In that case the carboxylic activating reagent is suitably selected from carbodiimides, acyl halides, phosphonium salts and uronium or guanidinium salts. More optionally, the carboxylic activating agent is an acyl halide, such as isobutyl chloroformate or pivaloyl chloride or a carbodiimide, such as EDC.HC1 or DCC.

Good results are often obtained when using additional carboxylic activating reagents which reduce side reactions and/or increase reaction efficiency. For example, phosphonium and uronium salts can, in the presence of a tertiary base, for example, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) and triethylamine (TEA), convert protected amino acids into activated species. Other reagents help prevent racemization by providing a protecting reagent. These reagents include carbodiimides (for example, DCC) with an added auxiliary nucleophile (for example, 1-hydroxy-benzo triazole (HOBt), 1-hydroxy-azabenzotriazole (HOAt), or Suc-OH) or derivatives thereof. Another reagent that can be utilized is TBTU. The mixed anhydride method, using isobutyl chloroformate, with or without an added auxiliary nucleophile, is also used, as is the azide method, due to the low racemization associated with it. These types of compounds can also increase the rate of carbodiimide-mediated couplings. Typical additional reagents include also bases such as N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), triethylamine (TEA) or N-methylmorpholine (NMM).

When the silylation is carried out in the presence of a solvent, said solvent is optionally a polar organic solvent, more optionally a polar aprotic organic solvent. An amide type solvent such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) or N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAC)

can be used. In the present invention for step 2, one can use an alkyl acetate solvent, in particular ethyl acetate is more particularly optional.

In the present invention for step 3, one can use a chlorinated hydrocarbon solvent or alkyl cyanide solvent, in particular dichloromethane or acetonitrile are more particularly optional.

In another embodiment, silylation is carried out in a liquid silylation medium consisting essentially of silylating agent and amino acid or peptide.

In the present invention, amino acid or peptide is understood to denote in particular an amino acid or peptide or amino acid analogue or peptide analogue which is bonded at its N-terminus or optionally another position, to a carboxylic group of an amino protected amino acid or peptide.

Example 3: Specifications for Compositions Containing Compounds of Formula (I)

1 ICH guideline Q3C on impurities: guideline for residual solvents

Example 4: Alternative Manufacturing of Trofinetide Example 1, Step 4, Procedure 4B

This Procedure is for a variant of Step 4, Procedure 4B. Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH (1 eq) was added in portions to Pd/C (0.027 eq by weight and containing 5% Pd by weight) in about 50 eq of water. The reaction mixture was hydrogenated at 20 °C at a pressure of 5 bar for at least 4 cycles of 4 hrs each. Pd/C (0.0027 eq by weight) was charged between cycles, as needed, to speed up the reaction. The conversion from Z-Gly-MePro-Glu-OH to trofinetide was monitored by HPLC. Upon reaction completion the catalyst was removed by filtration, washed with water (12.5 eq) and the aqueous layer washed with EtOAc (about 14 eq). After phase separation, residual EtOAc was removed from the aqueous solution containing

trofinetide by sparging with nitrogen under vacuum at 20 °C for about 3 hrs. The aqueous solution was filtered. The final concentration of trofinetide was about 25 wt% and the solution was then ready for spray-drying to isolate the product.

Example 5: Alternative Composition of Trofinetide

A composition comprising a compound of Formula (I)

or a stereoisomer, hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and a compound of Formula (II):

or a stereoisomer, hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and/or a compound of Formula (III):

or a stereoisomer, hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, wherein R1, R2, R3 and R4 independently are selected from the group consisting of hydrogen and C1-4 alkyl, provided that least one of R1, R2, R3 and R4 is C1-4 alkyl, and wherein the composition comprises at least 90 wt%, such as 91 wt%, 92 wt%, 93 wt%, 94 wt%, 95 wt%, 96 wt%, or 97 wt% of the compound of Formula (I) on an anhydrous basis.

Example 6: Alternative Composition of Trofinetide

A composition comprising a compound of Formula (Ia)

or a hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and a compound of Formula (II):

or a stereoisomer, hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and/or a compound of Formula (III):

or a stereoisomer, hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, wherein R1, R2, R3 and R4 independently are selected from the group consisting of hydrogen and C1-4 alkyl, provided that least one of R1, R2, R3 and R4 is C1-4 alkyl, and wherein the composition comprises at least 90 wt%, such as 91 wt%, 92 wt%, 93 wt%, 94 wt%, 95 wt%, 96 wt%, or 97 wt% of the compound of Formula (Ia) on an anhydrous basis.

Example 7: A Product of Trofinetide

A product, including a kit containing a dosage form with instructions for use, comprising a compound of Formula (Ia)

or a hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and a compound of Formula (IIa)

or a hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, wherein the product comprises between 95 wt% and 105 wt%, such as 96 wt%, 97 wt%, 98 wt%, 99 wt%, 100 wt%, 101

wt%, 102 wt%, 103 wt%, or 104 wt% of the specified amount of the compound of Formula (Ia) in the product.

Example 8: A Product of Trofinetide

A product, including a kit containing a dosage form with instructions for use, comprising a compound of Formula (Ia)

or a hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and a compound of Formula (IIa)

or a hydrate, or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, and additionally comprising one or more compounds selected from the group consisting of Formula (III), Formula (IIIa), Formula (IV), Formula (V), Formula (VI), Formula (VII), Formula (VIII), and Formula (IX), wherein the composition comprises between 95 wt% and 105 wt%, such as 96 wt%, 97 wt%, 98 wt%, 99 wt%, 100 wt%, 101 wt%, 102 wt%, 103 wt%, or 104 wt% of the specified amount of the compound of Formula (Ia) in the product.

Example 9: Analysis of Products and Compositions

The products and compositions disclosed herein may be analyzed by liquid chromatography, a suitable chromatographic method using UPLC, e.g. using materials and conditions such as Waters Acquity CSH C18, 1.7 µm, 150 x 2.1 mm column, water with 0.1 % TFA (mobile phase A), and water/ACN 70/30 + 0.1 % TFA (mobile phase B), ranging from (4% phase A/6% phase B to 100% phase B and flushed with 4% phase A/6% phase B).

Flow rate: 0.35 ml/min, Column temperature: 40 °C, autosampler temperature: 4 °C, injection volume: 4 ml (e.g. prepared by weighing about 10 mg of powder in a 10 ml volumetric flask and diluted to volume with water). Examples of detectors are UV (ultraviolet, UV 220 nm) and MS (mass spectrometry).

INDUSTRIAL APPLICABILITY

This invention finds use in the pharmaceutical, medical, and other health care fields.

PATENT

WO2014085480 ,

claiming use of trofinetide for treating autism spectrum disorders including autism, Fragile X Syndrome or Rett Syndrome.

EP 0 366 638 discloses GPE (a tri-peptide consisting of the amino acids Gly-Pro- Glu) and its di-peptide derivatives Gly-Pro and Pro-Glu. EP 0 366 638 discloses that GPE is effective as a neuromodulator and is able to affect the electrical properties of neurons.

W095/172904 discloses that GPE has neuroprotective properties and that administration of GPE can reduce damage to the central nervous system (CNS) by the prevention or inhibition of neuronal and glial cell death.

WO 98/14202 discloses that administration of GPE can increase the effective amount of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in the central nervous system (CNS).

WO99/65509 discloses that increasing the effective amount of GPE in the CNS, such as by administration of GPE, can increase the effective amount of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) in the CNS for increasing TH-mediated dopamine production in the treatment of diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

WO02/16408 discloses GPE analogs capable of inducing a physiological effect equivalent to GPE within a patient. The applications of the GPE analogs include the treatment of acute brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases, including but not limited to, injury or disease in the CNS.

Example

The following non-limiting example illustrates the synthesis of a compound of the invention, NN-dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid.

All starting materials and other reagents were purchased from Aldrich;

BOC = tert-butoxycarbonyl; Bn = benzyl.

BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid benzyl ester

To a solution of BOC-proline [Anderson GW and McGregor AC: J. Amer. Chem.

Soc: 79, 6180, 1957] (10 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 ml), cooled to 0 °C, was added triethylamine (1.39 ml, 10 mmol) and ethyl chloroformate (0.96 ml, 10 mmol). The resultant mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 minutes. A solution of dibenzyl L-glutamate (10 mmol) was then added and the mixture stirred at 0 °C for 2 hours then warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was washed with aqueous sodium bicarbonate and citric acid (2 mol l“1) then dried (MgS04) and concentrated at reduced pressure to give BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (5.0 g, 95%).

(7-Benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester

A solution of BOC-(γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (3.4 g, 10 mmol), cooled to 0 °C, was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (25 ml) for 2 hr at room temperature. After removal of the volatiles at reduced pressure the residue was triturated with ether to give (γ-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (I).

N,N-Dimethylglycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid

A solution of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 ml) was added to a stirred and cooled (0 °C) solution of (7-benzyl)-L-prolyl-L-glutamic acid dibenzyl ester (10 mmol), TVN-dimethylglycine (10 mmol) and triethylamine

(10.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (30 ml). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C overnight and then at room temperature for 3 h. After filtration, the filtrate was evaporated at reduced pressure. The resulting crude dibenzyl ester was dissolved in a mixture of ethyl acetate (30 ml) and methanol (30 ml) containing 10% palladium on charcoal (0.5 g) then hydrogenated at room temperature and pressure until the uptake of hydrogen ceased. The filtered solution was evaporated and the residue recrystallized from ethyl acetate to yield the tri-peptide derivative.

It will be evident that following the method of the Example, and using alternative amino acids or their amides or esters, will yield other compounds of Formula 1.

PAPER

Tetrahedron (2005), 61(42), 10018-10035. (CLICK HERE)

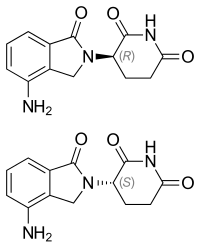

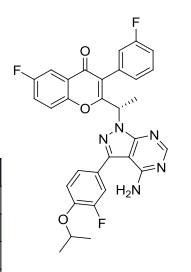

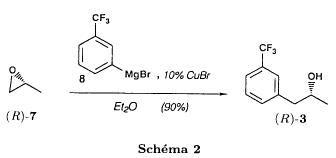

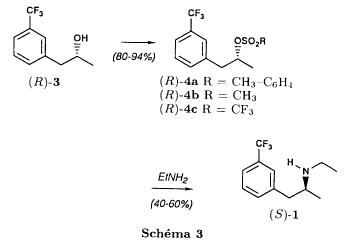

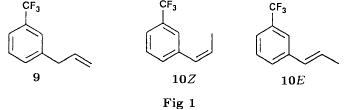

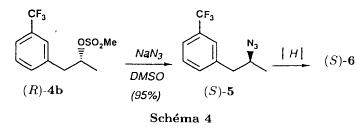

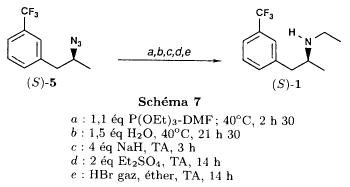

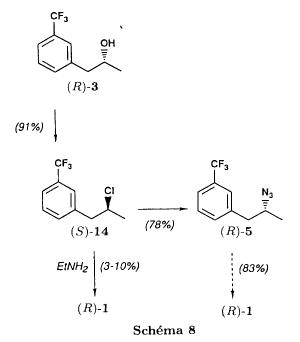

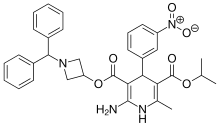

The synthesis of ten proline-modified analogues of the neuroprotective tripeptide GPE is described. Five of the analogues incorporate a proline residue with a hydrophobic group at C-2 and two further analogues have this side chain locked into a spirolactam ring system. The pyrrolidine ring was also modified by replacing the γ-CH2 group with sulfur and/or incorporation of two methyl groups at C-5.

Graphical Abstract

PAPER

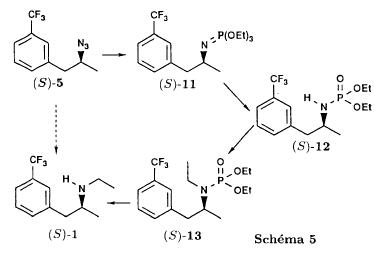

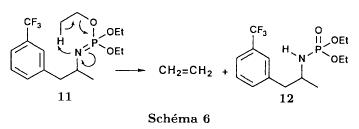

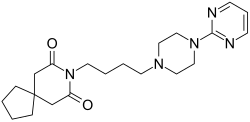

Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters (2005), 15(9), 2279-2283

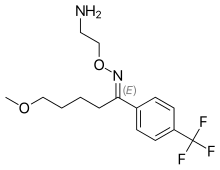

A series of GPE analogues, including modifications at the Pro and/or Glu residues, was prepared and evaluated for their NMDA binding and neuroprotective effects. Main results suggest that the pyrrolidine ring puckering of the Pro residue plays a key role in the biological responses, while the preference for cis or trans rotamers around the Gly-Pro peptide bond is not important.

Graphical abstract

A series of Pro and/or Glu modified GPE analogues is described. Compounds incorporating PMe and dmP showed higher affinity for glutamate receptors than GPE and neuroprotective effects similar to those of this endogenous tripeptide in culture hippocampal neurons exposed to NMDA.

PATENT

US 20060251649

WO 2006127702

US 20070004641

US 20080145335

WO 2012102832

WO 2014085480

US 20140147491

References

- ^ Bickerdike MJ, Thomas GB, Batchelor DC, Sirimanne ES, Leong W, Lin H, et al. (March 2009). “NNZ-2566: a Gly-Pro-Glu analogue with neuroprotective efficacy in a rat model of acute focal stroke”. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 278 (1–2): 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.003. PMID 19157421. S2CID 7789415.

- ^ Cartagena CM, Phillips KL, Williams GL, Konopko M, Tortella FC, Dave JR, Schmid KE (September 2013). “Mechanism of action for NNZ-2566 anti-inflammatory effects following PBBI involves upregulation of immunomodulator ATF3”. Neuromolecular Medicine. 15 (3): 504–14. doi:10.1007/s12017-013-8236-z. PMID 23765588. S2CID 12522580.

- ^ Deacon RM, Glass L, Snape M, Hurley MJ, Altimiras FJ, Biekofsky RR, Cogram P (March 2015). “NNZ-2566, a novel analog of (1-3) IGF-1, as a potential therapeutic agent for fragile X syndrome”. Neuromolecular Medicine. 17 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1007/s12017-015-8341-2. PMID 25613838. S2CID 11964380.

- ^ Study Details – Rett Syndrome Study

- ^ Neuren’s trofinetide successful in Phase 2 clinical trial in Fragile X

| PHASE | STATUS | PURPOSE | CONDITIONS | COUNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Enrolling by Invitation | Treatment | Rett’s Syndrome | 1 |

| 3 | Recruiting | Treatment | Rett’s Syndrome | 1 |

| 2 | Completed | Supportive Care | Injuries, Brain | 1 |

| 2 | Completed | Treatment | Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) | 1 |

| 2 | Completed | Treatment | Injuries, Brain | 1 |

| 2 | Completed | Treatment | Rett’s Syndrome | 2 |

| 2 | Terminated | Treatment | Concussions | 1 |

| 1 | Completed | Treatment | Brain Injuries,Traumatic | 2 |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status | US: Investigational New Drug |

| Identifiers | |

| IUPAC name[show] | |

| CAS Number | 853400-76-7 |

| PubChem CID | 11318905 |

| ChemSpider | 9493869 |

| UNII | Z2ME8F52QL |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H21N3O6 |

| Molar mass | 315.322 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | Interactive image |

| SMILES[hide]C[C@]1(CCCN1C(=O)CN)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)O)C(=O)O | |

| InChI[hide]InChI=1S/C13H21N3O6/c1-13(5-2-6-16(13)9(17)7-14)12(22)15-8(11(20)21)3-4-10(18)19/h8H,2-7,14H2,1H3,(H,15,22)(H,18,19)(H,20,21)/t8-,13-/m0/s1Key:BUSXWGRAOZQTEY-SDBXPKJASA-N |

////////////Tofinetide , NNZ 2566, PHASE 2, PHASE 3. NEUREN, Amino Acids, Peptides, Proteins,

CC1(CCCN1C(=O)CN)C(=O)NC(CCC(=O)O)C(=O)O

B1 IS DESIRED

B1 IS DESIRED

The action of d-camphoric acid on (rac)-fenfluramine (I) affords the camphorate of (+)-fenfluramine (II). After purification of this salt by crystallization, sodium hydroxide in methylene chloride is added, forming (+)-fenfluramine (III) after removal of camphoric acid. Finally, the action of hydrogen chloride in methyl cyclohexane on (+)-fenfluramine produces the corresponding salt: (+)-fenfluramine hydrochloride.

The action of d-camphoric acid on (rac)-fenfluramine (I) affords the camphorate of (+)-fenfluramine (II). After purification of this salt by crystallization, sodium hydroxide in methylene chloride is added, forming (+)-fenfluramine (III) after removal of camphoric acid. Finally, the action of hydrogen chloride in methyl cyclohexane on (+)-fenfluramine produces the corresponding salt: (+)-fenfluramine hydrochloride.

.HCl

.HCl

Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel; JCAR017; Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cells) is an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy designed to target CD19, [1][2] which is a surface glycoprotein expressed during normal B-cell development and maintained following malignant transformation of B cells. [3][4][5] Liso-cel CAR T-cells aim to target and CD-19 expressing cells through a CAR construct that includes an anti-CD19 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) targeting domain for antigen specificity, a transmembrane domain, a 4-1BB costimulatory domain hypothesized to increase T-cell proliferation and persistence, and a CD3-zeta T-cell activation domain. [1][2][6][7][8][9] The defined composition of liso-cel may limit product variability; however, the clinical significance of defined composition is unknown. [1][10] Image Courtesy: 2019/2020 Celgene/Juno Therapeutics / Bristol Meyers Squibb.

Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel; JCAR017; Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cells) is an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy designed to target CD19, [1][2] which is a surface glycoprotein expressed during normal B-cell development and maintained following malignant transformation of B cells. [3][4][5] Liso-cel CAR T-cells aim to target and CD-19 expressing cells through a CAR construct that includes an anti-CD19 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) targeting domain for antigen specificity, a transmembrane domain, a 4-1BB costimulatory domain hypothesized to increase T-cell proliferation and persistence, and a CD3-zeta T-cell activation domain. [1][2][6][7][8][9] The defined composition of liso-cel may limit product variability; however, the clinical significance of defined composition is unknown. [1][10] Image Courtesy: 2019/2020 Celgene/Juno Therapeutics / Bristol Meyers Squibb.